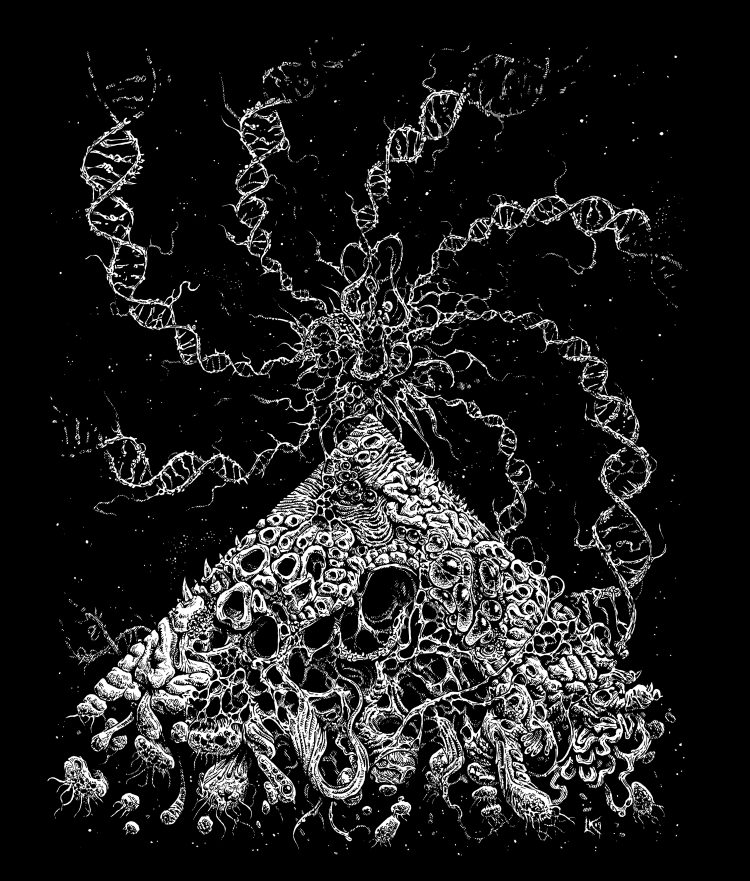

If you’ve been following death metal over the last few years, you’ve probably come across the incredibly detailed work of Lucas Korte. Under the moniker Shoggoth Kinetics, Lucas creates Lovecraftian depictions of inanimate matter that pull you in with their trickling tentacles and oozing orifices. Like a densely layered piece of music, you discover more about each drawing every time you interact with it. Every line has been placed there with intention and each viewing provides you with new perspectives of his work and the stark world he has crafted in black ink. After working with Lucas on a few projects, I learned about his extensive educational background and his ability to articulate his unique vision. Here are a few insights into the magnificently malefic mind of Shoggoth Kinetics.

When did you first realize you were an artist? Were you one of those kids that was always doodling in class?

I definitely was one of those kids. I got in trouble a lot for drawing in class, actually. I think I was maybe four or five when I started drawing. I really loved the old Ghostbusters cartoon when it was on TV, so even as a kid, I drew a lot of monsters. I also drew dinosaurs and robots and things like that, too, but definitely a lot of monsters. My parents were convinced I was just going through a phase! I kept making art through high school, but when I got into college, I didn’t really pursue it initially. I took some classes, but my family was supportive only to a point–they wanted me to be able to get a job, and an art career wasn’t considered financially stable by my parents. So, I went into science, thinking I might be a researcher or a teacher.

I still kept drawing, though. I started doing illustration stuff for the early-to-mid-2000s hardcore scene. I didn’t get paid a lot of the time, but I did do an early shirt design for Municipal Waste around the time Waste ‘Em All came out. But to get back to the first question, I actually don’t think I really thought of myself as an artist until I was in my 30s and back in art school. That was the first time, outside of playing music, that I really committed myself seriously to doing something with my life. I haven’t looked back since, though my work has evolved and my career has changed considerably since then.

You work with a lot of metal bands and currently have an impressive solo grindcore project called Infected Religion. How has being a metal fan and musician influenced your work?

I really think I got into metal for the same reasons I was really into Ghostbusters and monsters and gross-out stuff as a kid. I just liked that kind of thing. So, when I was in junior high, and I saw record covers for Slayer and Metallica and Megadeth, it just kind of pulled me in. I was already listening to the hard rock station on the radio, but the harder, faster stuff spoke to me even more than grunge. I still vividly remember the first time I put Reign In Blood on. It was like “holy shit, you can play music this way????” I was sold. It was a very short leap to death metal from there, and then my fledgling CD collection started growing by leaps and bounds. At that point, I was entranced by record covers by Wes Benscoter, Vince Locke, Jon Zig, and Dan Seagrave. So, that influenced the kinds of things I was drawing.

I was also dipping my toe into D&D at that time and the old 70s Monster Manual artwork also worked its way into my imagination. And, of course, I started reading Lovecraft around this time as well. I guess my early teens were kind of an awakening for me. As I got older, though, the same kinds of imagery and subject matter stuck with me. It’s always drawn my interest–there’s something about the less placid, weirder, and more obscure aspects of the universe and life that feels worthy of deeper exploration. Even as a biology major, my interest was primarily in invertebrate animals, because they’re so alien to our human experience of the world. I’ve always been fascinated by things that must have such a radically different way of existing. I think metal, and death metal, in particular, digs into those themes in a way that other genres don’t. I think that’s why I’ve come back to death metal and been immersed in it so many times over the course of my life. I keep coming back to it because the music and imagery approach the nonhuman side of the universe in such a visceral way.

I looked up the definition of Shoggoth and learned that it’s the name of an H.P. Lovecraft monster made of iridescent black slime with myriads of floating eyes that form and unform. What is it about Lovecraft that inspired you to focus on inorganic and nonhuman forms?

I think it’s because Lovecraft was the first thinker I ever encountered to treat Nature as fundamentally alien to human experience. Meaning, in his cosmology, conventional human philosophical or spiritual notions about the universe end up being superficial projections onto a much weirder, less comprehensible reality.

I think Mark Fisher put it best when he wrote about the difference between werewolves and black holes: werewolves are these fantastical creatures of superstitious darkness, but because they are inventions of the human mind, they follow cause-and-effect rules that are intuitive to us. But black holes actually exist, and their nature defies most of our common sense ideas about how objects should behave.

In a sense, Lovecraft was writing about black holes, not werewolves. His alien cosmology is a metaphor for a natural world that doesn’t conform to human systems, that is radically independent of the human mind, and within which we have an extremely limited perspective. With this as his intellectual ground, he created an aesthetically compelling nonhuman cosmos, or nonhuman nature, one which really got my artistic juices flowing when I first started reading him.

Is he the first, or most important, or most insightful voice talking about nonhumans in popular literature? Probably not. Are there deep flaws in his worldview? Absolutely, in fact, I think his racism is something of a motivation for his cosmology. It seems like a big coincidence that Lovecraft’s picture of the universe is a perfect inversion of the racist and anthropocentric Great Chain of Being popular in science and theology before that time. The Great Chain of Being goes something like this, in order of most to least ‘superior’: human beings on top (with white humans at the very top), animals beneath humans, plants beneath animals, nonliving matter at the bottom. But Lovecraft seems to have inverted this perfectly, having nonliving matter at the top–with entities like Azathoth seeming to be personifications of capricious and infernal materiality–then fungi and plant-like organisms (think of the Great Old Ones from At The Mountains Of Madness), then animal-like organisms (like the Deep Ones in The Shadow Over Innsmouth), then nonwhite humans (like the Cthulhu cultists), and finally, white humans seem to be the last people to know about any of this and so are on the “bottom.”

I think this reflects his anxiety about the loss of hierarchical social order in the world (not that this excuses his racism). I’d guess that in spite of his deep attachment to a rigidly racist social hierarchy, on some level he must have known this wasn’t the world we really lived in. His response, in part, was to flee into a reactionary mindset and a pessimistic philosophy. But the other part of his response was an aesthetically compelling fictive universe—one which laid the groundwork for other writers and thinkers interested, in one way or another, with the idea of a fundamentally nonhuman cosmos, populated with countless nonhuman entities, of which human beings are just one type of nonhuman.

So, I’m less interested in Lovecraft’s ‘cosmic pessimism’ and more interested in his cosmic nonhumanism, because there are more interesting places to go from there. The sheer inventiveness, variety, and vividness of his creations really fired my imagination at a time when I was receptive to them, and his intense visuality as a writer is a treat for anyone who wishes to draw monsters and alien gods. Shoggoth Kinetics itself is like a silly made-up science mapping the movements of shoggoths, or something like that, the shoggoth being one of those Lovecraftian entities that present particular problems for our all-too-human ideas about biology and the Tree of Life.

You have a BA in biological sciences and an MFA in fine art. What scientific approaches or considerations are involved in your artistic process?

My background in biology definitely plays a big role in the kinds of images I make. The biggest influence of biology on my work comes in the form of an ecological perspective–I tend to think of everything I do as a form of ecohorror. A major thing I learned in my time as a biology major is that all living things are in constant material exchange with their environments and with other organisms, boundaries between organisms are kind of arbitrary, and every organism is in some phase of flux between birth, growth, and decay. So, a lot of my imagery tries to use that basic underlying idea–things melting into other things, a lack of clear boundaries between bodies, bodies made of a hodge-podge of parts, and lots of imagery of decay.

I see all of this as ecological, but using the aesthetics of horror as a way of talking about how ecological relationships confound or contradict our sense of ourselves as unchanging individuals. If you’ve grown up under the paradigm of capitalist individualism, it can be uncomfortable, even threatening, to contemplate the idea that our individuality is an illusion, and that we cannot, in fact, exist without being entangled and embedded in networks of other living and nonliving things. Horror lets us explore difficult ideas and maybe even lets us get used to the truths they reflect. In the case of ecohorror, it’s that we are all temporary parts of larger networks, and we humans are all composed of countless nonhumans that form the basis of life. We will decay and return our materiality to the ecosystem, and we will be mixed and remixed within and through a host of forms of matter. There is no such thing as purity, and there are no clear boundaries between a body and its environment.

In the end, it’s a lot of fun for me to play with these ideas in visual form, to try to show, in some poor way, a reality that’s mostly invisible to us–to find fitting metaphors for exploring these ideas and to use the aesthetics of horror and the visual language death metal as a way to cope with and maybe embrace our slimy, contaminated, amoeboid existences.

You also use philosophy as a source of inspiration. Which schools of philosophical thought have influenced you most?

I encountered speculative realism when I was in grad school and that really changed my outlook in some fundamental ways. Speculative realism is an umbrella term for a bunch of different schools of thought, some of which conflict with each other, but they all basically look for a way out of our ingrained anthropocentrism and all try to ground our understanding of the universe in terms of the nonhuman.

The one school that I was and still am most influenced by is New Materialism. Without getting into too much technical stuff, New Materialism (NM) tries to do away with the hierarchies we’ve used to categorize the universe. So, for instance, when I was talking about Lovecraft’s inversion of the Great Chain of Being, NM would just argue that there is no Chain of Being in the first place–nonliving matter is no more or less than living matter, plants are no more or less than animals, humans are no more or less than anything else. NM thinks of everything in terms of physical matter, but a physical matter which is not inert and passive, waiting for humans to mold a world out of it–instead matter is active, creative, subversive, capricious, promiscuous, even destructive. In this conception, humans may mold the world, but at the same time, matter is molding humanity. After all, your body is composed of matter, and it’s only by virtue of matter that we have brains in the first place. Both see things in the universe as fundamentally equal, not, as the philosopher Graham Harman puts it, “humans in one box and everything else in the universe in a second, equally-sized box.”

The materialism stuff is influential for me because it’s a useful extension of the scientific materialism I picked up as a student of biology, and it also makes way for the ecological ideas that come out in my work. In terms of metal music and horror, I find the idea of everything being composed of the same virulent, putrid, chaotic, and fluctuating matter to be endlessly fascinating. I think it makes for great imagery. This outlook is how I think about the universe whether I’m drawing up decaying zombies or Lovecraftian monstrosities–and in some ways, it perfectly encapsulates a horrifying materialism.

As a professor at the University Of Notre Dame, you teach painting and drawing classes. How much of your personal tastes do you share with your students? Does your career empower you and your students to share new influences with one another?

Well, I try to show my work to my classes each semester, to give them an idea of where I’m coming from. My work is pretty different from what the typical Notre Dame student is used to, and it usually sparks a good conversation about where ideas come from and how to become an illustrator, but I think mostly I’m a bit of a curiosity to my students. It’s a pretty conformist campus. I’ve met a few metalheads in my time there, mostly among the grad students, staff, and faculty, but almost none of the undergrads listen to anything harder than Panic At The Disco (I’m not entirely sure why that’s still a popular band with them). From time to time, I make them listen to whatever I’m feeling while we’re working in the classroom. That might mean Siouxsie And The Banshees, or it might mean Hyperdontia.

Broadly, though, I do try to expose them to as much weird and challenging art as I can, because they usually come into my classroom with a very narrow idea of what art is, of what’s acceptable, etc. I love to show them artists like Caroline Harrison or Christian Van Minnen and watch their eyes get wider. They usually haven’t seen anything like that. Of course, with teaching, it definitely is a two-way street and many times my students have led me to artists that I hadn’t encountered before.

What are some of your favorite pieces that have ended up on record covers or merch? Are there any upcoming projects that you are looking forward to?

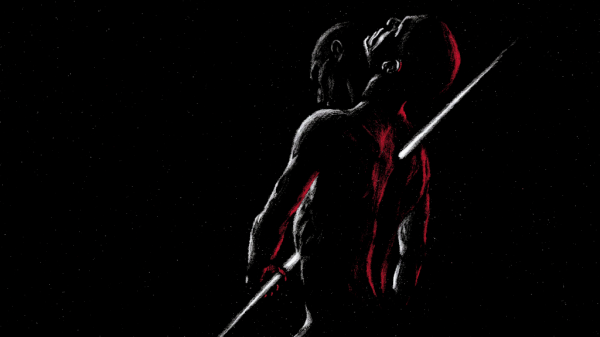

For recent stuff, I’m really excited about the split EP between my band Infected Religion and Mark Riddick’s band Fetid Zombie. The whole thing came out killer, but the cover art was a dream come true–to get to do a physical artwork collaboration with Mark was a huge high point of my career so far, and he is one of the nicest dudes I have met.

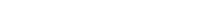

Next up, I’d have to say I’m very happy with the cover painting for Universally Estranged’s debut LP. It was awesome to be part of such an exciting piece of modern death metal history, and I’m really proud of how my piece came out and how well it fits with the music.

I’m also quite happy with the cover illustration I did for Stench Collector’s debut record which is due out on June 25th via Redefining Darkness. The concept was so unique, so fun to visualize and draw, and the band was really excellent to work with.

collaboration with Mark Riddick, 2020, ink on paper, 8.5 x 10”

Do you have any wisdom you can share with those looking to create art of their own?

Figure out what you’re interested in. I don’t look at my time studying biology as a detour. It’s been a huge source of inspiration and ideas for me, as well as the starting point for my whole outlook on art and the world. It can be an enormous struggle for artists to find a voice when they haven’t looked deeply enough into the world outside of art or music. It’s the unique blend of influences and interests that makes every artist different.

The other thing I would say is to just keep at it. This is advice that was actually given to me years ago by Justin Bartlett (of Vberkvlt fame). I pestered him with an email asking for advice on being an illustrator and he was kind enough to answer it. He told me to make work no matter what’s going on, don’t wait for a client to come to you. You’ll never generate interest by waiting around, nor will your work improve. I took that advice to heart and it worked.

Thanks so much for the interview, Davey! It was a lot of fun.

Donate to Justin Bartlett’s Gofundme to help him out with his cancer treatment if you can. Thanks for reading!!!

Check out Shoggoth Kinetics on Instagram.