How the youth culture mutated and spread across the borders of the conservative state

Pinched from Dazed Digital

In 1978, the Turkish rock musician Tünay Akdeniz informed the country’s press – to subsequent horror – that his band were “punk rock.” Akdeniz was mostly sporting a bad boy image to push record sales rather than to make political history (his music was probably closer in style to glam or hard rock), but his words nevertheless made a huge impact. Before then, no musician in Turkey had dared describe their band as punk.

In the 1970s, Turkey saw rising tensions between the left and the right, resulting in a 1980 coup d’etat during which hundreds were rounded up to be killed, arrested, and imprisoned. With punk seen as part of an antagonistic, anti-establishment youth culture, there were risks of violence from both police and the nationalist far-right for associating yourself with it. 40 years on from his comment, Akdeniz now explains that “youngsters could only secretly lose their heart to rock music and listen to it from cassettes on the quiet.”

Akdeniz believes that there was no real punk movement in Turkey – certainly not in the same directly confrontational and anti-authoritarian sense as the British one. “The Sex Pistols sing, ‘she ain’t no human being’ about Queen Elizabeth in ‘God Save The Queen’,” he explains. “In Turkey at the time, you couldn’t imagine attempting something like this. The same is true even now. If you do, in the best scenario, no one plays your song. In a worse scenario, you find yourself engaged in a lawsuit.”

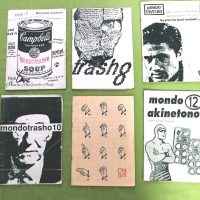

Given this backdrop, it’s hardly surprising that little written history on punk’s small but potent presence in the country’s youth culture existed until recently. The book An Interrupted History of Punk and Underground Resources in Turkey 1978-1999 elaborates on the sporadic presence of the genre and youth culture movement – visually, musically, and socially – in the country. With the genre associated with nihilism and teenage delinquency in the popular consciousness, those who took on the mantle of punk were either brave or reckless.

That’s not to say that political music didn’t exist in Turkey in the 20th century, but it took on guises more embedded in traditional Turkish folk, with the most iconic example being Selda Bağcan, a singer popular among left wing activists during the 70s for songs that expressed solidarity with Turkey’s working class population. She was imprisoned three times between 1981 and 1983, but continued to write political songs, including the lament “Uğurlar Olsun” for the assassinated journalist Uğur Mumcu in 1993.

In the case of some bands, like Tampon and Rashit in the 90s, their flavour of punk was more of a left wing rebellion. Conversely, some on the Turkish left saw punk as a sign of individualism creeping in from the west.

CASSETTES REVOLUTIONISED THE SCENE

Full recordings of punk albums didn’t fully emerge in Turkey until cassettes appeared in the 80s. “In the end of 80s, we were using cassette tapes, or if some people were lucky they were using portable studios, which were multitrack recorders using cassette tape,” says Murat Ertel. “This was a select few: they taught the younger generation things such as the link with punk and ska and popular groups like Athena were born like this. Normal studio recordings for punk music were unheard of before 90s.”

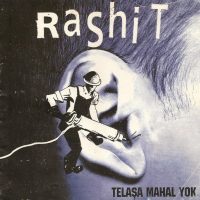

The 90s saw the formation of bands like the politically charged, proto-feminist Tampon, whose frontwoman Asli voiced concerns over the safety of women in the streets, freedom of movement, and capitalism. Until 2017, Tampon were never in a position to record the music they played live in the 90s. Their contemporaries Rashit, however, were in such a position, and their 1996 album Kadıköy’den Hareketler was one of the first rock records in Turkey to contain overt anti-racist and humanitarian messages.

In 1994, the same year that Tampon formed, hardcore punk and metal-influenced bands like Radical Noise, Necrosis, and Turmoil all went abroad to have their records produced. There was also a key Turkish language resource for punks – sociologist Dick Hebdige’s Subculture: The Meaning Of Style, which examined resistance through youth subculture in postwar Britain, was translated in 1988.

Tolga Özbey, who formed Rashit in the 90s, says that his reasons for getting into heavy rock were entirely political. “The reason why punk couldn’t be so popular in Turkey was because of the military coup in 1980. All has changed since and it was a big trauma for us as a country… It’s still hard to walk in the streets freely; there’s too much pressure on us by both police or by fascists. I attacked a newspaper, and the prime minister and general Kenan Evren (the military officer who assumed his post by leading the 1980 coup) who said ‘I don’t want a punk generation.’ At the beginning of the 90s, young people began to get excited about making music again – but mostly apolitical music, more like metal.”

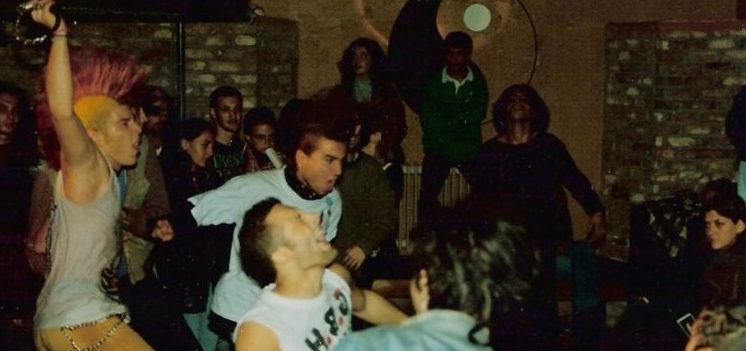

So that meant that even in the 90s, it was difficult to perform in a punk band in Turkey and Rashit’s performances were classic examples of when this went awry. “Our first gig at 1993 in Üsküdar, in an apartment’s basement. 40 to 50 people showed up, and the police came to stop the gig because of noise. After so many concerts we played for Çekul Vakfı’s Sultanahmet Square concert in 1995, and and once again the police stopped the concert because of the anarchist lyrics. I remember another festival which we were playing at an open air concert called European Music Days in 1998 – fascists attacked the stage, police shut the electricity off and we were hospitalised with broken arms and legs. In the 00s, things briefly changed, and everything turned into money nobody cared about any politics for a long time – until 2013 Occupy Taksim Square, it was damn good to see.”

For the full story head to Dazed Digital