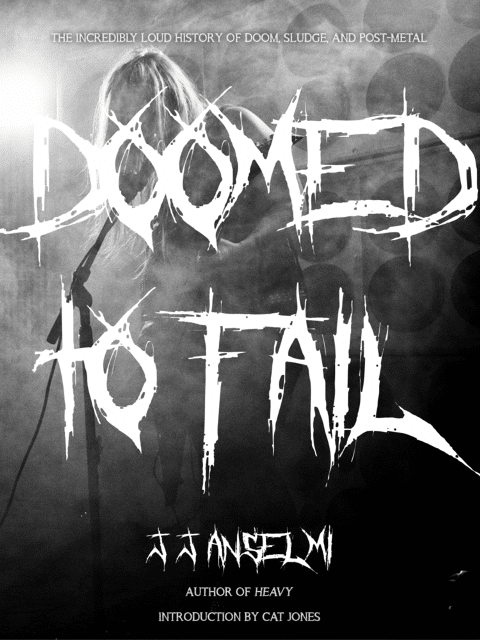

On February 11, 2020, Rare Bird Books will release Doomed to Fail: The Incredibly Loud History of Doom, Sludge, and Post-metal, from author and musician J.J. Anselmi. Today we’re stoked to be able to share the chapter focused on Miami sludge band CAVITY, so if you’re a sludge fan you better read on! You can pre-order it here via Indie Bound.

Sweat and Swagger

Tampa, 1993. You came out to see Eyehategod and Buzzoven but there’s an opener you haven’t heard: Cavity. As you watch the band set up, you think, “These guys just look like regular Joes. How heavy could they be?” With their tattoos, grungy hair, and out-of- it demeanor, the members of Eyehategod and Buzzoven look like what you expect sludge metal musicians to look like: ex-cons. The members of Cavity are the type of guys you see but don’t really register on the street—normal haircuts, plain t-shirts, maybe a few tattoos, but nothing crazy. They’re all business as they set up their instruments and check vocal levels. Then they nod at each other and a wild cat vibe courses through the room. The guitarists and bassist turn on their amps and unleash piercing feedback, keeping their backs to the crowd. The vocalist wrestles with his mic stand as the rest of the band saunters into slow, plodding hardcore. The singer suddenly crashes into the drums, knocking down two cymbals. Everything stops.

“Fuck you, Rene,” the drummer yells. And then to his other bandmates: “I hate that fucking guy. That’s it. I’m not playing with him anymore.” He’s tensed up like a coiled snake but walks backstage instead of punching his singer. The other band members look at each other. The bassist and guitarists walk backstage, which is just a back corner behind a ratty curtain. You and the rest of the crowd—about fifty people—can hear what they’re saying.

“I’m not going back. I hate that guy.”

“Dude, you have to come back, we’ve got a show to do.” “We’re going to get paid. We have to do this, we’re performing.” “We can’t just do the intro and quit.”

He still refuses. The guitarists and bassist come back and talk to their singer, who’s just been standing onstage awkwardly, listening to the exchange and knowing he shouldn’t talk to the drummer himself. They collectively shrug their shoulders and pick up their instruments. Before they start playing again, Jimmy Bower of Eyehategod yells out, “I’ll play drums.” The members of Cavity look at each other like, Fuck it, might as well, and then Bower is behind the kit. Whatever they’re going to play, it’ll be interesting.

The dense Florida air is charged. Bower holds his sticks in the air, starting the count: “One, two, three…” But then the drummer is back, saying he’ll finish the set. Bower laughs and hands him the sticks. As if nothing happened, Cavity launches into blazing punk that sounds like The Descendants playing through Melvins’ amplifiers. The drummer is visibly pissed. Face red, he’s beating the hell out of his drums. Cavity steers that dirty hardcore riff into a brick wall, gutting the tempo and leaving it to crawl across the floor. Rene howls with kinetic violence, sounding like a trucker getting whipped with motorcycle chains—and kind of liking it. The crowd becomes a seething mass, similar to the audience when you saw Cro-Mags. The band is playing individual songs, but the set feels like one continuous burst. You get elbowed in the face but don’t care. You get punched in the ribs but don’t care. Someone spills beer on your shirt and you kind of care. It must be the last song because Cavity’s guitarists and bassist throw their instruments to the ground. They start messing with the knobs on their amps and pedals to produce this horrible feedback.

Jaime Salazar

You realize the singer is missing. There’s a loft above the stage, and you hear a hurried shuffling up there. Someone grunts and you can see a mattress teetering on the rail, about to fall onto the stage. Rene is up there trying to push a stained mattress over the rail. He eventually gives up and collapses in a heap. The band members turn off their amps. They take a few breaths but then start hauling their gear off stage like nothing happened. They’re drenched in sweat; otherwise, you’d have no idea they just played such an intense set. It was pure, unfiltered aggression, the likes of which you’ve only seen in a handful of hardcore bands.

“Things were pretty volatile for us back then,” Dan Gorostiaga, bassist and stalwart member said about Cavity shows throughout the nineties. “Anything could happen.” He and Rene Barge started the band around 1992. He recalled,

Even before then, like in the mid-eighties, we were going to hardcore shows down in Miami. We’d see bands like The Exploited, Seven Seconds, Youth of Today, and a bunch of others. We had a big venue in Miami, so all the touring bands would make the trip down there, which was crazy. Miami is the last point on the map, basically. I guess their guarantees must’ve been good. All the big bands would come through: Cro-Mags, Descendants, All. So that was our high school, basically. When I went to high school, I didn’t have many friends myself. All my friends went to other high schools, and we’d congregate at this place every weekend. You’d get to know a lot of people. There were posers, people there just for the fashion, but also a lot of people there for the music. You had the weekend skinheads and weekend punks with their mohawks. We met a lot of people there and started playing in bands. My friends and I were more active than a lot of other people, because we wanted to get involved and start bands and fanzines.

After playing in a few hardcore bands, Gorostiaga started to meld metal and punk in a group called Killer Kane. He appreciated the heaviness of Sabbath and Deep Purple, but he didn’t like the rock star attitude so prevalent among metal musicians. To him, Cavity was always closer in spirit to Karp, Am Rep-style noise punk bands, and proto-metalcore acts such as Rorschach.

It was around the time when bands like Born Against, Citizen’s Arrest, and Rorschach were popping up. We were all just kids playing music. Karp popped up, and I would compare us with that crowd. We got lumped into the whole metal thing, but if you see us live it’s really different. A lot of bands have that metal image, the long hair and all that. We weren’t like that at all. Birthday Party and the Laughing Hyenas were also big influences. It was people just doing whatever they wanted. I was in Killer Kane for about three months and then we broke up.

Rene was around during that time. He used to work at this local record store. When I told him that my band broke up, he was like, “Oh man, I’ve been wanting to sing. Let’s get together and do something.” We were listening to a lot of the Am Rep and Touch and Go stuff, as well as other stuff that was more underground. It was a mix of punk influences as well as a bit of metal, I guess—the darker stuff. But we were more influenced by bands like Karp. That’s the main band I would compare us to as far as where we were coming from. They played heavy music but were also just regular Joe-looking kids. We just didn’t fit the image of the whole sludge metal thing.

Part of what Gorostiaga and Barge didn’t like about metal was the separation between the band and audience, especially with bigger bands. If there weren’t barricades and security, members of those bands inhabited the stage like it was an elevated realm. Cavity wanted to confront audiences, striving for a collective exhalation of anxiety. “Metal for us wasn’t really on our radar,” Gorostiaga said. “We were way more about in-your-face shows in backyards and basements, not in big clubs with barricades and bouncers. We didn’t grow up in that environment. The whole punk thing was about being there all together, and it was really immediate. And we were all the same. There wasn’t the separation you see in metal.”

Cavity released its self-titled tape in 1992, following that with the Scalpel seven-inch a year later. Both recordings include core members Gorostiaga and Barge, as well as drummer Joey Iglesias and guitarist Raf Luna. Those releases pulse with nervous misanthropy, putting the band on the radar of underground music fiends across the US. Cavity put out its first LP, Human Abjection, in 1995, which features drummer Jorge Alvarez, who plays on most of Cavity’s LPs. Much of that record lumbers in midtempo sludge, sounding like Noothgrush bumped up a few BPMs. Sections of feral powerviolence and hardcore—always filtered through tar— also pop up on Human Abjection. Alvarez’s raw drumming injects urgency into every song. Throughout the LP, Barge howls like he’s just chugged a tall glass of bleach. In addition to John Bonanno, Steve Brooks of Floor plays guitar on Human Abjection, starting Cavity and Floor’s long-running tradition of sharing members.

Considering the amount of feedback-drenched sludge that’s found its way into the world these days, it’s easy to underestimate just how confrontational Cavity was, especially during its early years. If crowds of the time were reacting to Eyehategod with outright hostility, the same must’ve been true for Cavity. Miami has long been known for its club scene and dance music. If a Miami DJ played Human Abjection in 1995, he would’ve cleared the club and lost a gig, and quite possibly gotten his ass beat. Cavity wouldn’t have had it any other way. Miami punks saw their city’s club scene like kids from Vegas see the strip: as a blight. But it made for a common enemy, galvanizing the community. Gorostiaga said that people in Miami who played in aggressive bands made it a point to support each other.

There were two or three places to play in Miami. We were just a bunch of regular people, and we all knew each other and would go to each other’s shows. So it was easy to be in and out of bands. It was a small scene filled with people that wanted to play music. There were a bunch of short- lived bands. The big venue closed down, so we started going to this place called Churchill’s Hideaway. They’d let anyone book shows there. That’s how we met Floor. Their drummer Betty [Monteavaro] played with us for a little while. We didn’t have a drummer, so she filled in for one show for us and then stuck around for a record. Floor was the other main heavy band in Miami. We got to know each other, and then Anthony [Vialon] started playing with us. Steve recorded Human Abjection with us. He did a few shows with us and then he got busy with Floor. Floor was the main band we switched members with. There were bands called AAA and then The Crumbs, and people from both those of those bands played with us at some point.

Cavity unleashed the Crawling seven-inch the same year as Human Abjection, compiling songs from both releases, plus a few new ones, on 1996’s Drowning, which is basically three different EPs, recorded during different sessions, put together. With Gorostiaga and Alvarez on every song, the first half of the record features Anthony Vialon of Floor on guitar. The second half finds Vialon on vocals, leaving guitar to Bonanno, Ed Matus, and Brian Bush. About Cavity’s routine lineup changes, Gorostiaga said, “Cavity has really been a revolving door with members, and that made a big difference on each record.” Since the band’s music is all about feel and vibe, each player heavily impacted Cavity’s output. While Gorostiaga thinks the band “could have grown a bit more with permanent members,” he also recognizes that those changes kept Cavity from stagnating. More so than guitarists, he said, the group’s sound has been shaped by its drummers. After Human Abjection, Alvarez’s drumming started to take on a woozy swing in the spirit of Chris Hakius and Joey LaCaze. That feel is the foundation for 1997’s Somewhere Between the Train Station and the Dumping Grounds, Cavity’s most blues-soaked record up to that point. The album simultaneously pulses with hardcore’s tenacity and unpredictability.

Coming from the South, at least some blues influence was inevitable for Cavity. But Gorostiaga doesn’t think of Cavity as a Southern sludge band, at least not in the same way as Eyehategod or Buzzoven. “Miami is not a Southern town in the typical sense,” he said. “There’s just so much going on. It’s in the South, but you also get people who think and act like New Yorkers, although they live in Miami. A lot of people doing weird, avant-garde stuff. You have a lot of influences. It’s just a huge melting pot.” At the same time, place always has an influence on musicians, consciously or not. “The Southern type of sound wasn’t really something we were looking for, it just sort of happened,” the bassist stated. “We’d want to play something simple, and maybe the riff would sound more bluesy for whatever reason. It wasn’t intended, it just sort of came out.”

But Cavity’s take on the blues has been minced by a blender with Black Flag, Void, and Minor Threat for blades. From “Goin’ Ann Arbor” to “Shake ‘Em on Down,” the band weaves in and out of a filthy swing, periodically leaping forward in anxiety-ridden punk. Sludgecore gets thrown around when it comes to classifying Cavity, and that’s most apt when applied to songs such as “Your Funeral, My Time.” It speeds forth in virulent hardcore, stops on a dime, and then plows through mud. Taking cues from Noothgrush and Grief, tracks like “One Last Broken” seethe with agonized hopelessness. Somewhere Between the Train Station and the Dumping Grounds is a brilliant record, in no small part because of Barge’s no-holds-barred vocal attack. Timing and placement-wise, his yells and screams claw with the unpredictability of a cornered badger. Just when it seems like he’s veered too far into his own world, he punctuates exactly the right note to transform a riff’s jab into a knockout punch.

In 1997, Cavity released a handful of seven-inches and of course went through lineup changes, with Alvarez temporarily bowing out. After recruiting Juan Montoya (later of Torche) on guitar and Betty Monteavaro of Floor on drums, the band entered Morrisound Studios to record Laid Insignificant, which wouldn’t see light until 1999. According to Gorostiaga, Monteavaro contributed largely to the record’s panic-inducing feel. “For Laid Insignificant, Betty from Floor played with us,” he said. “That one was really fast, and she worked well for that. She kind of gave us a new identity in a way. We had another guy named Dan Norris, and he did the Sabbath and Germs covers. Everything sounded a lot different with each drummer.” As for her percussion on Laid Insignificant, Monteavaro sounds like she’d been drumming for Spazz in addition to Floor. Vitriolic hardcore sections in the title track, “9 Fingers on the Spider,” and “Spine I” are pushed by punker blasts, with Monteavaro inhabiting the spearhead of the beat. Her snare is tuned high, which enhances the nineties powerviolence feel of the record. When the fast parts derail into sludge, it’s crushing every time. Monteavaro plays half-time beats with the swagger of Chuck Biscuits, throwing in fills that match Barge’s vocals in their unpredictability.

“I May Go” opens with somber instrumentation, similar to the uneasy soft sections of Neurosis’ Souls at Zero. Barge belligerently barks into the microphone, sounding like a disgruntled roughneck. The band eventually meets the vocalist’s intensity with serrated chugs, making “I May Go” the closest thing Cavity has to a ballad— but it’s bastardized, wallowing in nihilistic self-loathing instead of whimsical longing. If we’re going to use sludgecore as a label, Laid Insignificant should be filed as the sub-subgenre’s idealized form.

Throughout the Between the Train Station…and Laid Insignificant years, Cavity never toned down its live shows. Gorostiaga recalled,

We’d sometimes play with our backs toward the audience to mess with people, or we’d start that way and then turn around. It was loud with a lot of feedback and noise, super loud. All the shows were pretty crazy. We could start with one song and then just do three and that’s it. Everything would end for some reason. Either the way we were feeling toward the music or the audience—it would just be done. There were always just a bunch of unpredictable factors. Every show was really its own performance, dictated by the environment or anything else.

Again, not to rag on metal, but it all seemed pretty staged to us. The performers didn’t move much on stage. There’s kind of a formula that they follow. We wanted it to be more avant-garde. We’d have shows randomly with three guitar players. We’d do new stuff all the time. Once we had a problem with a guitar player and he got left behind on tour, so we just did a show as a three-piece: bass, drums, and vocals. So we had all kinds of crazy stories. As far as playing live, every show was unique.

After recording Laid Insignificant, Cavity signed with Man’s Ruin, a prominent underground label of the time. But that achievement was accompanied by major setbacks: Barge decided to part ways with the band, and Monteavaro vacated her drum spot. Not willing to pass up a deal with Man’s Ruin, Vialon stepped up to perform vocals in addition to playing guitar and writing songs. Cavity enlisted guitarist-vocalist Ryan Weinstein and Floor’s powerhouse drummer, Henry Wilson, on drums to round out the lineup for SuperCollider.

Released by Man’s Ruin in 1998 and then reissued by Hydra Head in 2002, SuperCollider might be Cavity’s best-known album. True to Gorostiaga’s idea that the band’s sound was always molded by its drummer, Wilson’s fat, no-frills backbeat is that album’s center of gravity. His behind-the-beat grooves put Cavity’s riffs on pedestals, setting them up to worm into permanent memory. Vialon shouts with punctuated clarity, also following clearer patterns than Barge and his edge-of-sanity wails. All told, SuperCollider is a bit more palatable than the band’s previous efforts, though it’s far from an easy listen. “Xtoone” is nails-on-the-chalkboard noise, and “Damaged IV” trudges through swampland like a member of Grief looking for a place to dump a body. That said, Barge’s absence is felt on SuperCollider. It’s a solid record, but it underscores how large of a role the singer played in giving Cavity its raucous and unpredictable feel.

In 1998, the group contributed to Hydra Head’s multi-volume series, In These Black Days: A Tribute to Black Sabbath, paving the way for Cavity to work with the label again to reissue SuperCollider and put out 2001’s masterful On the Lam. After some time away, Barge and Alvarez entered the fold again. Vialon and Wilson shifted their focus to Floor as that band geared up to record and release its self- titled album, and Weinstein stuck around on guitar.

It’s fitting that Hydra Head put out On the Lam: it’s metalcore, but not at all in the generic sense, making Cavity a perfect addition to a roster that’s included Coalesce, Converge, and The Dillinger Escape Plan. From “Cult Exciter” on, On the Lam moves with a loose violence, carrying the intensity of Cavity’s unhinged performances. The song begins with a vicious punk ’n’ roll stride and then sidesteps into greasy, up-tempo swing. Barge’s voice crackles like he’s yowling through a loudspeaker. Throughout “Cult Exciter” and every other track, he yells with a slight drawl, combining with Weinstein’s whiskey-marinated riffs to make On the Lam a Southern sludge record, through and through. Alvarez leads Cavity into tempo shifts and breakdowns in a way only a human drummer could. No grid in sight, just dirty metal whose edges bleed. About three-quarters of the way through “Cult Exciter,” Weinstein and Gorostiaga repeat a gap-toothed riff over and over, filling in the space with expertly deployed feedback. They take what many musicians see as a mistake and turn it into its own mode. It doesn’t get much more punk than that. Fifth cut “Willy Williams” utilizes that same tactic when it degenerates into a minutes-long squall.

On the Lam is one of those albums that paints a defined setting from the get-go—and it never steps out of that world. “Boxing the Hog” starts with a side-eye riff that delivers on its title’s promise, creating an undeniable urge to punch a hog. “Sung From a Goad” jogs in angular punk reminiscent of Laid Insignificant, and then “Pulling Up the Stakes” menacingly swerves between double and half-time with Alvarez always at the wheel. On paper, both tracks have a lot in common with stoner rock, a genre that’s gotten watered down to the point of losing relevance. “Sung From a Goad” features a swaggering solo, and the switch between between half and double-time within the same riff in “Pulling Up the Stakes” was used by every stoner rock group from the nineties. But Cavity’s fangs shoot venom into those cliché moves. That’s the blues for you: two different guitarists can play the same exact notes, but one’s playing will make your blood boil while the other’s will put you to sleep.

“Pulling Up the Stakes” finds additional power in its nod to metalcore. As the song transitions into increasingly slower sections, “breakdown” might not be the word that comes to mind, but that’s what’s happening. The members of Cavity saw firsthand how Rorschach, Converge, and Coalesce’s breakdowns short-circuited people’s brains. It follows that the band would put its own spin on that tactic, as well as taunting buildups, to maximize impact. Seventh song “Leave Me Up” features Cavity’s most rib-crushing breakdown. At the end, a tough hayseed riff cycles, slowing down multiple times, like it’s getting beat up in a bar fight until all it can do is crawl. Screaming group vocals add weight to each repetition. It’s not hard to imagine how “Leave Me Up” might move an audience to pile on top of each other in a massive group sing-along—but this one’s for weird hick kids instead of jockish New Englanders.

“On the Lam” is the paint-huffing sibling of Laid Insignificant’s “I May Go” in its antagonistic linger. While a quiet drum and bass groove slithers, Barge takes center stage with his unintelligible, loudspeaker croon. “I May Go” feels like he’s picking a fight with you. “On the Lam” sounds like he’s picking a fight with the universe, his aggression latching onto everything in its path. Weinstein waits behind the corner with barely-perceptible feedback, taking his sweet time before unleashing a riff with alligator jaws. Time and again, On the Lam weds the aggravated punk spirit of Laid Insignificant with the swagger of Somewhere Between the Train Station and the Dumping Grounds, making it the perfect bookend for Cavity’s first life.

Cavity didn’t see the glorious implosion you might expect, especially given its history as a live band. As Gorostiaga remembered it, the band members just started to lose interest after On the Lam came out.

We broke up back in 2001, after we put out On the Lam. We’d try to book tours and someone would back out. People were pulling in different directions for different reasons. So I decided to go to school. We did one last show in Tampa with Cutthroats 9. We also did a few with High on Fire before then. But we had to do some of those shows without Rene because of his job in the film industry. When a shoot starts, they have strict schedules and can’t get time off. We did a mini tour in Florida with High on Fire as a three piece. Jason Landrian, the guy from Black Cobra, was playing guitar and singing for us then. Then Rene came back and we did a few more shows. The one in Miami went well, but then Tampa was a mess again. It was so loud the drummer couldn’t hear what was going on. And then at some point, Rene just disappeared. He went to the bathroom during the set. So we were all pulling in different directions. Some of us wanted to get more serious, but we just decided to call it at that point. We were all planning to move. We just couldn’t keep it together.

Gorostiaga moved to New York for school and focused on that for the next several years, eventually getting his MFA. People would still ask him about Cavity, though. When he returned to Florida, he got the itch to play again.

I moved back to Florida after finishing my MFA, and I did approach Rene and Anthony, but they weren’t really into it. I kept getting show offers though, so I kept asking them. In 2015, a good friend of ours from Miami got in a freak accident. She was on top of a ramp, and the ramp collapsed. She fell down and got paralyzed, basically. She can’t move her thighs. She was looking to buy a custom van and wanted to do a fundraiser show, and she wanted Cavity to play. So I asked everyone and they were really into it. That’s what got the whole thing rolling again. We did the reunion show, and then we just decided to keep playing music. We wrote After Death with Ed Matus, who’s been playing guitar with us for a while. We had Rick Smith from Torche fill in on drums for us for a few shows, but he’s the type of guy who’s playing in like three or four bands at once—who are all touring. So it can be hard to get a hold of him since he’s so busy. We did After Death with just me, Ed, and Rene. Ed did most of the drumming.

We don’t want to go out there and just rehash the past. The reception to After Death was pretty mixed. Everything was done in a studio where I’d record bass tracks, and then we’d put everything on top of the bass tracks. Since then we’ve still been writing. We just finished four new songs.

It’s not hard to understand why After Death would throw people for a loop. Matus pounds out minimal tom rhythms, giving the album a punishing, nigh-industrial vibe. After Death also veers into threatening quiet with unexpectedly light instrumentation— think Cavity channeling Neil Young. It’s mellow compared to the band’s previous efforts, but like anything Barge and Gorostiaga do, there’s a lurking menace.

Cavity might never be as violent or prolific as it once was. If After Death and 2019’s Wraith are any indicators, however, the band will continue to release music that refuses to be ignored. Having perfected their ability to recede into the blur of mundanity, Barge and Gorostiaga both teach high school. These days, Gorostiaga lives in a sleepy fishing town called Stuart. He sometimes surprises his students by showing them Cavity records or videos of old shows. Otherwise, kids probably think he’s just a cool art teacher. It’s a fitting life for someone who always approached hardcore with a regular Joe mentality: look plain but play music that destroys people. They won’t expect it, which makes the beating that much more memorable.

Pre-order Doomed to Fail here via Indie Bound.

Doomed to Fail explores the heaviest music the world has ever heard, tracing doom, sludge, and post-metal as their own distinct (and incredibly loud) traditions. Anselmi covers the bands and musicians that have impacted those styles most–Black Sabbath, Candlemass, Melvins, Eyehategod, Godflesh, Neurosis, Saint Vitus, and many others–while diving into the cultural doom that has spawned such music, from the bombing of Birmingham and hurricane devastation of New Orleans to glaring economic inequality, industrial alienation, climate change, and widespread addiction. Along the way, Anselmi interweaves the musical experiences that have led him to proudly identify as one of the doomed.