The author would like to thank Signal Culture, where this essay was written during a summer Researcher in Residence period, and to Drexel University’s Center for Interdisciplinary Inquiry for its presentation.

“Charlie, Charlie, can we play?” begins the incantation to invoke a demon of the same name using the simple tools of pencils and paper. Recently, the hashtag #CharlieCharlieChallenge began trending throughout social media, local and national news media outlets. Reaction videos featuring, largely, teenagers playing the game, and becoming frightened by the supposed interaction with a demon began to be viewed and shared in the thousands. The success of the #CharlieCharlieChallenge resulted in schools (of various continents) banning it, and religious leaders denouncing it as evil and Satanic.[1][2] Meanwhile, Reverend Bob Larson performs exorcisms over Skype,[3] and the network Destination America has announced EXORCISM: LIVE! will air on Halloween of 2015.[4] While it may appear contradictory for religion, spiritualism, mysticism, magic and the occult to co-exist with our current information technology, looking back into history we find that these subjects are in fact major factors in the development of techno-culture, as well as future developments with respect to transhumanist and greater posthumanist ideologies. The medium will always be haunted.

Bob Larson exorcizes a demon possessing a young man in Norway using Skype and duel screens / mirrors. Originally aired on CNN. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=Ej4sHU0xfwE

Origins of a Demon

1936: Actors Brian Donlevy and Claire Trevor try out a Ouija board while on break from filming Human Cargo. | (AP Photo) found at http://theweek.com/articles/451347/secret-ouija-board

A telling aspect of the game Charlie is its own confusing, historical and cross-cultural roots, which are claimed to originate in Spain, with variants played throughout other Spanish speaking countries, where for generations students have played a paper-and-pencil game called juego de la lapicera.[5][6] The goal of the game, played primarily by female students, is to learn who “likes” you (and it does not feature a demonic force). I refer to gender here only because there is a relevant history of such patriarchal heteronormative rules and outcomes in much folklore, witchcraft and spiritualism, or mediumship,[7] including that which appears to be the origins of Charlie. While clearly the history of talking, or spirit, boards like Ouija[8] inform Charlie, there is also a longer lineage of folklore and legend that results in the current techno-bricolage. The most obvious is the game of Bloody Mary, or witch in the mirror. A form of necromancy and mirror divination – calling on a spirit or demon in order to learn of the future – the rules consist of entering darkened rooms (often bathrooms) and chanting “Bloody Mary” three times (this number may vary significantly and I remember throwing water on the mirror as one variant). The figure of Bloody Mary is now mostly considered malevolent – with references to fortune telling being very few. Although there is no definitive origin of Bloody Mary, various strands of folklore and legend repeat similar themes: Queen Mary I of England, known for mass executions of Protestants, as well as for her numerous miscarriages; perhaps also her confusion with purported serial killer, Elizabeth of Bathory, the noble woman convicted of enslaving, torturing, killing and bathing in the blood of young women; the Mexican tale of La Llorona, the ghost of a woman who is said to have drowned her children in a river in Mexico after learning of her husband’s infidelity (with a younger woman) – she drowned herself in the same river; and finally, the husband divining ritual described by Bill Ellis, where a young woman walks backwards upstairs while holding a mirror and a candle in order to see an image of their future husband (apparently powered by a witch).[9] If a skull appeared, they would instead die alone.[10] With the addition of juego de la lapicera, where young women seek to confirm the love of another male, each draws patriarchal heteronormative gender role distinctions and rules. For the older tales, an aged, childless, single woman is left to depression, suffers infidelity, and the haunting or murdering of the young, who in turn learn to fear a similar demise as they look through the mirror – where the witch is perhaps an anti-world version of themselves.[11]

“Divination rituals such as the one depicted on this early 20th century Halloween greeting card, where a woman stares into a mirror in a darkened room to catch a glimpse of the face of her future husband, while a witch lurks in the shadows, may be one origin of the Bloody Mary legend.” from “Bloody Mary” Wikipedia entry; Reproduced in Bill Ellis, Lucifer Ascending: The Occult in Folklore and Popular Culture (University of Kentucky, 2004). ISBN 0-8131-2289-9

Charlie takes many of these elements: pencil and paper, necromancy (ask the demon a question) without the patriarchal narrative. In order to play, a piece of paper is divided into four quadrants by drawing a cross. Players then write yes and no, and stack a pencil atop another before asking, “Charlie, can we play?” The rest of the game involves various yes/no questions, with the spinning pencil pointing to the demon’s response. In order to end the game you must ask Charlie, “Can we stop?” But who is Charlie? Apparently, it is an “ancient” Mexican demon – of which there is no history of such a demon existing. Importantly, the game is essentially dependent on being broadcast and shared via the social network. In this respect, I argue that the element of Vine, or the sharing of the game, is not simply a document, but rather an important rule of Charlie that must be performed in order to properly invoke the demon – it is a ritual. Therefore, something must be said of the medium, or technology, which facilitates the spread of the new digital demon.

The Medium is the Metaphysics: postinternet spiritualism & the dead

With this context, it is understood that Charlie is not entirely new, and neither then is the interest in playing with dark subjects. “The games of people reveal a great deal about them,” writes Marshall McLuhan in a chapter on games –interestingly, given the subtitle of “Extensions of Man,” which is repeated in the title of the important work of Understanding Media: The Extensions of Man.[12] Clearly then, games are extremely important to McLuhan, and it appears the reason is that games act as an outlet, both physical and psychical, in mediating between “individualist Western man” and the “’adjustment’ to society” which “has a character of personal surrender to the collective demands.”[13] McLuhan continues, “Our games help both to teach us this kind of adjustment and also to provide release from it.”[14] And for folklorist Ellis, games “are transcriptions of serious, real-life concerns, and their play-like elements often allow these concerns to be expressed more directly than they would be in passing conversation.”[15] What is different is the medium; therefore, what is the message? “The form of any game is of first importance… Any game, like any medium of information is an extension of the individual or the group,” explains McLuhan.[16] Once we decipher what the medium of Charlie is, we may better understand what it may mean with respect to magic and techno-culture.

By medium, or media, I mean the sort McLuhan had in mind, which is often synonymous with technology acting as an extension of ourselves: mind, body, social interaction, and so on. Therefore, a medium always refers to another medium. In the case of electronic media, according to McLuhan, we extend our central nervous system and consciousness. With respect to our topic, however, I also refer to necromancy or the channeling of the dead through a person or thing acting as a medium. This medium is the leading figure, or source of power, which leads a séance in either speaking for or conjuring the dead, for example. Thus, the medium is the intermediary between life and death. In both cases, medium and the message are problematized. In the social web, what is the medium: Twitter, Vine, World Wide Web, or the greater Internet? Clearly, it is multi-media, with their parts being extremely fluid and relational, and with all referring to one another and the earlier media they extend. I have used multiple terms for our present condition – social web and techno-culture – but I’d also like to borrow a term used largely in contemporary art: postinternet. While the term has proven problematic for art critics and theorists, Gene McHugh’s description of a condition where the distinction between making art on or offline becomes more ambiguous, or essentially nonexistent, is I believe similar to the way Westerners can describe their own social lives as a network that is always connected, no matter physical or graphical. Performing online or offline is no longer a question. And what of the medium of the spiritualist, the medium that conjures the demon? What is their content? Is it the living? Is it digital re-tribalization through folk tale and communal spiritualism expressed as digital, or media folklore?

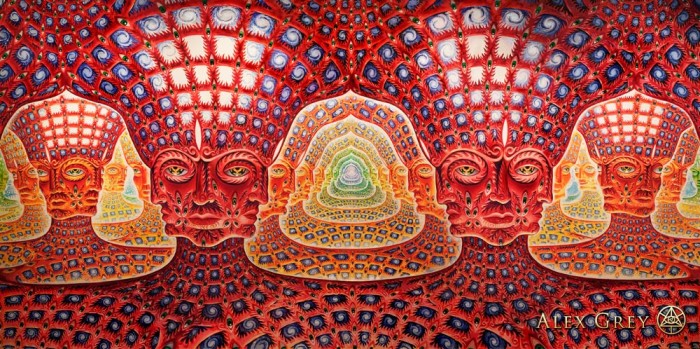

Net of Being, Alex Grey, 2002-2007, oil on linen, 180 x 90 in. http://alexgrey.com/art/paintings/soul/net-of-being/

While the human medium of the traditional spiritualist sense still exists, with Charlie, the private space of the round table with friends and family has broken, and instead, the event or performance takes place primarily to be documented and shared, live and publically as per the postinternet condition. The medium here, between the players and the demon, is the network and its applications: Vine, Twitter, YouTube, et al. Gone is the medium figurehead, or magician (photoshoppers are the new illusionists). Instead everyone can potentially tap into the other side. Charlie, then, is the first demon of the postinternet. The relationship between technology and ghosts, or ghosts-in-the-machine, is not new either. Media theorist Jonathan Sterne, writing of early sound documentation and reproducibility as a result of the advent of phonography, explains how progress in aural archiving coincided with improvements in archiving the human body through embalming techniques. He writes, “…if sound reproduction simplifies vibration in new ways, if we learn to ‘hear’ other areas of the vibrating world, then it would make sense that we might pick up the voices of the dead. In this formulation, the medium is the metaphysics. The metaphorization of the human body, mind, and soul follows the medium currently in vogue”[17]; today, that is postinternet social communication technology. Sterne continues, “…media are forever setting free little parts of the human body, mind, and soul. If the voices of the dead were, indeed, free agents, perhaps they could then be enticed back into the world of the living.”[18] Jeffrey Sconce, in Haunted Media, describes this kind of techno-American spiritualism empowered by the “spiritual telegraph”:

American Spiritualism presented an early and most explicit intersection of technology and spirituality, of media and “mediums.” Enduring well beyond a fleeting moment of naïve superstition at the dawn of the information age, the historical interrelationship of these competing visions of telegraphic “channeling” continues to inform many speculative accounts of media and consciousness event today…the contemporary legacy of the Spiritualists and their magical technology can be found in sites as diverse as the “psychic friends” network, Baudrillard’s landscape of the hyperreal, and Hollywood’s current tales of virtual reality come alive and run amok.[19]

“The Celestial telegraph, 1853. Partridge & Brittan in New York . In 1854 a group of Spiritualists petitioned congress for the money to copy Morse’s telegrapgh development with a way to communicate with Spirit by Telegram.” found at Medium Mediums: http://www.mediamediums.net/en/projects

In the Victorian age, when sound recording was first introduced (1878), “death was everyone” explains Sterne, and as a result, spiritualism – a merging of religion and science – was a respected “major cultural force.”[20] While a similar status has not existed for some time in America, present postinternet culture expresses its own form of techno-spiritualism with a coupling of science and spirituality. Except, rather than simply communication – or reanimating the dead as avatars – techno-culture also wants to live forever. Futurist Ray Kurzweil ponders death and the importing of our consciousness into machines in search of immortality:

A related question is, “Is death desirable?” A great deal of our effort goes into avoiding it. We make extraordinary efforts to delay it, and indeed often consider its intrusion a tragic event. Yet we might find it hard to live without it. We consider death as giving meaning to our lives. It gives importance and value to time. Time could become meaningless if there were too much of it.

…

But I regard the freeing of the human mind from its severe physical limitations of scope and duration as the necessary next step in evolution. Evolution, in my view, represents the purpose of life. That is, the purpose of life—and of our lives—is to evolve…

So evolution moves inexorably towards our conception of God, albeit never reaching this ideal. Thus the freeing of our thinking from the severe limitations of its biological form may be regarded as an essential spiritual quest.[21]

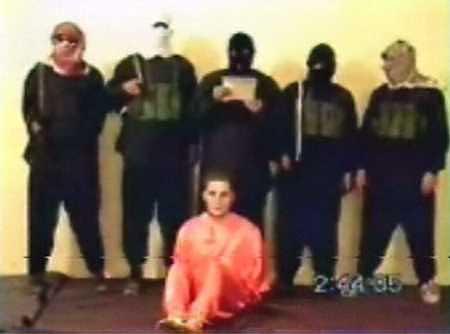

With decades of death saturating the screen – from televised images of the Vietnam War entering the family living room, to YouTube beheadings streamed everywhere at anytime – it could be said that death is everywhere again; death is nowhere; death is shared. Where would the Jihadists be without their Internet performances of beheadings as they yell “Allahu Akbar”? Technology spreads and informs the message. Writing in the Sexual Chaos: Chaos, Magic, Cybersex and Religion for a Postmodern Age, Hugh B. Urban describes the postmodern esotercism, magick, and an occult practice called Chaos Magic, whose contemporary practice is supported by those technologies that gave rise to the postinternet.[22] Chaos Magic is “an explicitly syncretic and iconoclastic approach,” which “ draws freely on any and all practices that seem useful, while at the same time rejecting any absolute claims to truth and regarding all beliefs as so many relative illusions.”[23] He continues, “It is no accident…that the rise of various forms of Chaos Magic occurred at roughly the same time as the birth of the intellectual movement of postmodernism and deconstruction.”[24] By postmodernism, Urban refers back to Jean Francois Lyotard’s description: a rejection of metanarratives, or grand theories of reality and history (modernism), an emphasis on spontaneity (e.g. chaos theory), play and shock, expressions of irony and parody, or pastiche, and aesthetics of radical eclecticism. Lyotard even describes postmodernism as a form of paganism, one that is radically eclectic, where adherents (if one could be called such) choose and cobble together their own bricolage of world views –a hybridity whose formation is not dissimilar from Charlie the demon’s origins, and in fact, the life and times of folklore throughout history.[25]

“Nick Berg seated, with five men standing over him. The man directly behind him, said to be Zarqawi, is the one who beheaded Berg.”https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Nick_Berg

And what of the medium? “It is perhaps no accident that one of the most effective and popular media for the dissemination of new magical styles like Chaos Magic is this shifting, fluid, transient, and radically eclectic network of the World Wide Web,” explains Urban.[26] Urban continues, “Indeed, the rapidly proliferating, highly syncretic, and inherently fleeting nature of the Web would seem to make it in many ways an ideal vehicle for constantly morphing self-deconstructing movement like Chaos Magic.”[27] As Urban and others have noted, in fact, the rise of new-age, and neo-paganism finds its birthplace in similar quarters to Silicon Valley techno-utopianism of 1960s counter culture.[28] Therefore it is no surprise or contradiction to have cyberpagans and technopagans playing an important role in the earliest developments of a more social Internet and Web. Mark Pesce, the inventor of VRML (Virtual Reality Modeling Language of the early World Wide Web [1994]), is a well-known example of a technopagan. In the early 1990s, Pesce made the connection between the construction of a virtual space and witchcraft, for example. Speaking to Wired, Pesce describes witchcraft as applied cybernetics. He explains, “It’s understanding how the information flow works in human beings and in the world around them, and then learning enough about that flow that you can start to move in it, and move it as well,” and “Without the sacred there is no differentiation in space; everything is flat and gray. If we are about to enter cyberspace, the first thing we have to do is plant the divine in it.”[29] Pesce put his technopaganism to practice, by performing one of the first group rituals he called CyberSamhain, “a ritual held simultaneously in cyberspace and in real space” and coinciding with the 25th anniversary of the Internet. Pesce writes:

One of the philosophical arguments I was making at that point was that there is no fundamental difference between the virtual world and the shadow realm, in other words, the dreamtime. And what I wanted to do was to say, “Okay, if the god is in the shadow, he can also be in the dreamtime of cyberspace.” And so the ritual was constructed around welcoming the god into cyberspace, because that was the time for entering. Remember, time is one of the essences of witchcraft. So this seemed the right thing to do.[30]

Bloody Mirrors: Performing Digital Demons

During the 1980s, psychedelic guru of the 1960s, Timothy Leary turned his attention to techno-culture. As mentioned above, it is no surprise that Leary’s philosophy of consciousness-raising hybridity would find a friendly partner in what would be called the cyberdelic movement. As a pre-transhumanist, Leary became more interested and involved in coupling “turn on, tune in drop out” with “turn on, boot up, jack in” to the future of personal computing, the Internet, and virtual reality for its promise of a new progressive-spiritual cyber human and an extended life as expressed in one of his last works Chaos and Cyber Culture (1994). When, in 1995, Leary was diagnosed with inoperable prostate cancer, he began using his homepage as a proto-blog detailing his experience with dying, or designer dying. In fact, Leary planned on “broadcasting the world’s first ‘visible, interactive suicide’ over the World Wide Web” (New York Times).[31] In a 1996 web article, writing for The New York Times, Edward Rothstein describes Leary’s intentions as “tapping into some of the more disturbing tendencies in the Web,” where, “the private world dissolves; what remains is a public show. The Web, in fact, relies on the breakdown of bounds between private and public; it creates a sense of a large community as well as absolute isolation. The public and private realms become illusions: there is no guaranteed community and no real privacy,” and finally, “television, of course, has already broken down many of the boundaries between public and private in its confessional talk shows. Human oddities and social outcasts are sought out by the producers who follow the examples set by the old circus side shows. But the Net goes further, creating the illusion of privacy in a very public place.”

Dr. Timothy Leary next to a PC, which he called the LSD of the 1990s. Image: Esquire http://www.esquire.com/news-politics/news/a24830/timothy-leary-papers-released-to-public/

Rothstein’s analysis and critique of the public-private concerns of the Web are prescient, as today we are concerned not only with our personal surveillance and over-sharing, but with the nefarious tales of government and business tracking of our everyday lives. It is a tele-visuality that Paul Virilio warns of in The Information Bomb. When the time came for Leary to die, there was no live, interactive stream. There was no final performance of death, as was promised. In fact, Leary also pulled out of plans of being cryogenically frozen. No – in the end, his last minutes were recorded, but never broadcast. Of course, broadcast suicide over the Internet was already happening in the 1990s, and there were suicide forums, and websites devoted to shock and gore – not much different than today. In recent years, the sharing of information or the bullying over the network has led some to suicide; in some instances, the social suicide notes or the documentation of death are the result of the interactive and performative nature of the network as Leary foresaw. In other instances, as Geoff Cox notes, the virtual suicide of our online identities may be one of the most important political acts of the present postinternet.[32] Now, the most consciousness-raising act may be to disconnect and drop out of the network, or, to recognize the narcosis of the medium, as McLuhan suggests.

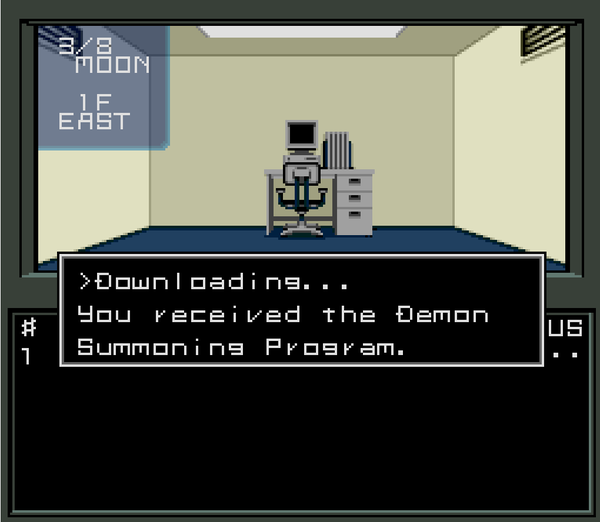

With social media, our daily interactions are interactive and performative. The success of Charlie, then, is connected to this idea of play, capturing one’s reaction and sharing it, with those who share then becoming participants in the spreading of the demon. It’s role-playing. But the shock of the performance, of the possibility that Charlie may be communicating, may fulfill the sobering effect of reminding the game players that realities are fluid, that the technology is fallible. The 1987 role-playing video game, Digital Devil: Megami Tensei is known as one of the first to dispel with medieval themes and instead focus on cyberpunk subject matter. The game features computer programs and hackers that summon or fuse demons through the network and bring them into real-life. The game of Charlie expands upon these themes of the digital demon. “Computers are simply mirrors,” explains Pesce. “There’s nothing in them that we didn’t put there. If computers are viewed as evil and dehumanizing, then we made them that way. I think computers can be as sacred as we are, because they can embody our communication with each other and with the entities – the divine parts of ourselves – that we invoke in that space.”

Digital Devil Story: Megami Tensei (Famicon, 1987) video game; Screen shot capture by the author June 2015.

In the postinternet condition, it is difficult to argue against the computer as a mirror – the confusion comes from which side the reflection is coming from. Every day, we participate in this new divine mirror – our anti-selves – shared and performed, we look in and out at ourselves. In this case, then, we might expand upon earlier folklore by turning out the lights, illuminating the dark with the fire of our mobile devices, and then stare at our social media profile(s) while repeating, “Bloody Mary, Bloody Mary, Bloody Mary.”

[1] “Why the Education Ministry Has Banned the Charlie, Charlie Game in Schools,” The Gleaner, May 29, 2015. Accessed July 1, 2015, http://jamaica-gleaner.com/article/news/20150529/why-education-ministry-has-banned-charlie-charlie-game-schools

[2] “Pat Robertson Warns Against Charlie, Charlie Challenge: Demons Will Possess and Destroy You,” May 29, 2015. Accessed, July 1, 2015, http://www.rightwingwatch.org/content/pat-robertson-warns-against-charlie-charlie-challenge-demons-will-possess-destroy-you

[3] CNN, https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=Ej4sHU0xfwE

[4] The program claims to be the “first-ever televised exorcism” but in 1991, 20/20 aired an exorcism on the ABC network, https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=FLcYtHRZn9k and http://www.destinationamerica.com/tv-shows/exorcism-live/

[5] Phil Edwards,”Charlie, Charlie, are you there? Why teens are summoning demons, explained,” Vox, June 5, 2015. Accessed July 1, 2015, http://www.vox.com/2015/6/5/8735481/charlie-charlie-challenge-explanation

[6] Caitlin Dewey,“The complete, true story of Charlie Charlie, the ‘demonic’ teen game overtaking the Internet,” The Washington Post, May 26, 2015. Accessed July 1, 2015, http://www.washingtonpost.com/news/the-intersect/wp/2015/05/26/the-complete-true-story-of-charlie-charlie-the-demonic-teen-game-overtaking-the-internet/

[7] Bill Ellis, Lucifer Ascending: The Occult in Folklore and Popular Culture (University of Kentucky, 2004) and Jeffrey Sconce, Haunted Media: Electronic Presence from Telegraphy to Television (Duke, 2000).

[8] Patented in 1892 by William Fuld, a Baltimore customs worker; Sconce, 180. One day, while Fuld was working atop one of his factories, he fell to the ground, breaking his ribs in the process. One of his ribs pierced his heart resulting in his death.

[9] Ellis, 146-152.

[10] Ellis, illustrated image of a Halloween card featuring the mirror ritual, uploaded by user Smerdis of Tlon, Wikipedia, https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Bloody_Mary_(folklore)#/media/File:Halloween-card-mirror-2.jpg

[11] Ellis, 167.

[12] Marshall McLuhan, Understanding Media: The Extensions of Man (New York: McGraw-Hill, 1965, 238).

[13] Ibid.

[14] Ibid.

[15] Ellis, 143.

[16] McLuhan, 242.

[17] Sterne, 88.

[18] Ibid.

[19] Sconce, 25.

[20] Sterne, 291.

[21] Ray Kurzweil, Are We Spiritual Machines? (Discovery Institute, 2001), http://www.kurzweilai.net/chapter-1-the-evolution-of-mind-in-the-twenty-first-century

[22] Hugh B. Urban, Sexual Chaos: Chaos, Magic, Cybersex and Religion for a Postmodern Age,

[23] Ibid, 19.

[24] ibid, 223.

[25] Urban, 226.

[26] Ibid, 223.

[27] Ibid, 223-4.

[28] Richard Barbrook and Andy Cameron, “The California Ideology,” Imaginary Future, http://www.imaginaryfutures.net/2007/04/17/the-californian-ideology-2/

and Jacob Silverman, “Meet the man whose utopian vision for the Internet conquered, and then warped, Silicon Valley,” The Washington Post, March 20, 2015, https://www.washingtonpost.com/opinions/how-one-mans-utopian-vision-for-the-internet-conquered-and-then-badly-warped-silicon-valley/2015/03/20/7dbe39f8-cdab-11e4-a2a7-9517a3a70506_story.html

[29] Wired, http://archive.wired.com/wired/archive/3.07/technopagans_pr.html

[30] Pesce, http://hyperreal.org/~mpesce/ctnsinterview.html

[31] http://partners.nytimes.com/library/cyber/techcol/0429techcol.html

[32] Geoff Cox, “Virtual Suicide as Decisive Political Act,” http://www.lesliensinvisibles.org/les_liens_uploads/2011/01/suicide.pdf