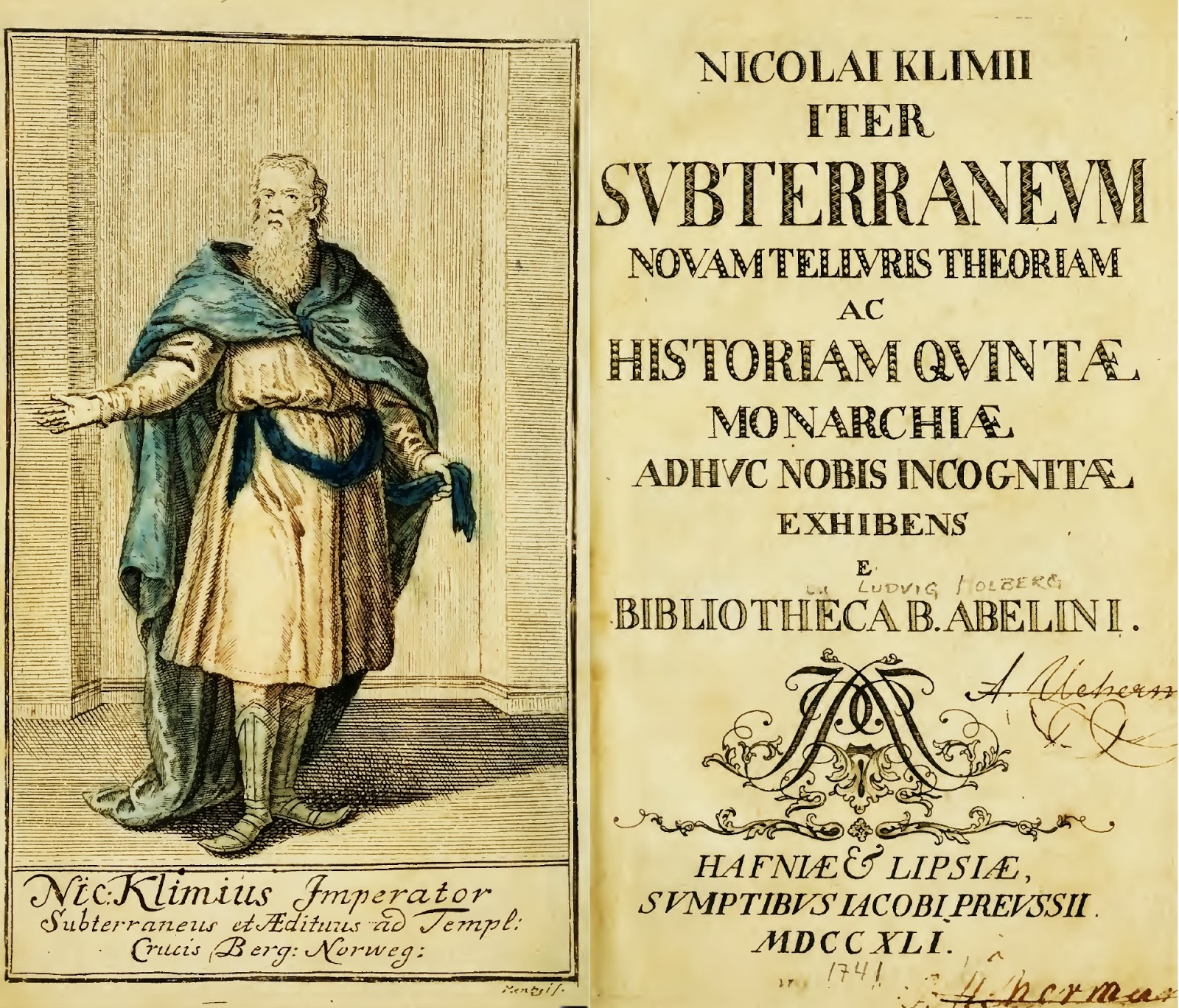

Ludvig Holberg’s 1741 Latin novel, The Journey of the Niels Klim to the World Underground presents a far-ranging satire of European society through an imaginary voyage of a young college graduate as he travels throughout a series of fantastic worlds beneath the earth’s surface. Utilizing the freedom of an imaginary world, the novel circumvented the strict censorship of its day to become something of a best-seller in Germany and Scandinavia. The eponymous Niels Klim approaches each society with an unwavering sense of his own superiority, and that of his homeland, only to be continually humiliated and ridiculed. The satire of the work emerges from the conflict between the naïve bravado of Klim and the different societies and values he encounters. Effectively, the novel circumvents potential censorship and backlash by seemingly reinforcing European values and supremacy, only to indirectly dismantle this perspective with the reason or foolishness of the elaborate fantasy worlds the narrator encounters.

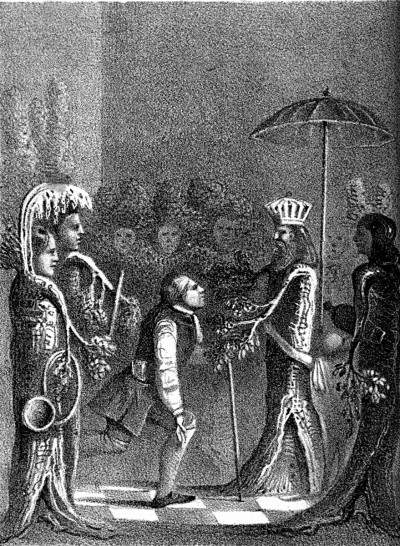

Niels Klim finds himself accidentally in a subterranean world, having fallen while exploring a cave on the surface. In this underground world, Klim visits a number of worlds in the novel; most strikingly is the planet Nazar inhabited by enlightened tree people. Their home kingdom of Potu (Utopia) is a striking example of 18th-century Enlightenment thought, with all its associated blessings and curses. The Potuans allow Klim to remain in their society after an initial altercation, on account of his “so weak and uneven a judgment that he hardly merits to be considered as a rational creature”, and take advantage of his relatively mobile form by employing him as a royal messenger.

In this role, he witnesses a myriad of strange peoples and societies, some strange and terrible, other marvelous and interesting; in one land, all the inhabitants are born with different numbers of eyes and divided accordingly. One trip nicely encapsulates the novels manner and themes:

“The most numerous and of course the most powerful tribe… have oval eyes, and to whom consequently all objects appear oval. From this tribe are taken the senators, the priests, and all such as bear office in the state. These sit at the helm, nor do they admit anyone from another tribe to a post in government unless he shall first confess, and confirm his confession with an oath, that a certain tablet dedicated to the sun and placed in the most conspicuous part of the temple appears to him to be oval… Hence the honester part of the citizens, who start at perjury, are excluded from all public honours… and though they over and over protest that they cannot disbelieve their eyes, they are still complained of, and what is only a fault of nature is imputed to their obstinancy and malice” (1).

Refusing to leave the matter at that, Klim seeks out the tablet himself “with all the eyes I had, and really it appeared square to me. This I ingenuously told my host… With that he fetched a deep sigh and confessed to me that it appeared square to him too, but that he dare not say so publicly, for fear of being dispossessed of his employment by the governing tribe” (2). Klim is quick to condemn this unforgivable hypocrisy, but as is his way throughout the novel, he moves on, leaving reflection to the wayside.

Klim’s service for Potua comes to an end when, fed up with what he sees as a lowly position unfit for a man of his learning, he attempts to secure a prestigious position by asserting the superiority of himself and his gender to a female official (3); failing his case and offered the choice of exile or apology, Klim refuses contrition “out of respect to mankind, upon whose character such a confession [of human weakness] would leave an indelible blemish” (4). Thereafter Klim finds himself banished, and strangely at home with a society repellent but strangely familiarly intelligent apes, and later a land of wild men who Klim decides to instruct in the ways of “civilization” with disastrous results.

Needless to say, the novel contains numerous further travels and anecdotes, ridiculing the oppressive conformity and hierarchy of the 18th century. As a piece of Enlightenment era fiction, The Journey of Niels Klim to the World Underground strides the thin line between the permitted and the condemned, the superficial and the philosophical, the fantastic and the real. The novel is a firm reminder how even in the face of oppression, censorship, and hierarchy, a glimpse of anarchistic freedom resides within the world of comedy and satire.

– – – –

The Journey of Niels Klim to the World Underground is available at Project Gutenberg, where the 19th-century translation can be found: http://www.gutenberg.org/ebooks/27884

A more recent corrected translation is available in paperback and was used for references in this article.

– – – –

References:

(1) Ludvig Holberg, The Journey of Niels Klim to the World Underground, edited with introduction by James I. Mc Nelis Jr., (Lincoln: University of Nebraska Press, 1960), 86.

(2) Ibid., 122 – 123.

(3) Ibid., 125.

(4) Ibid., 125.