Time really does fucking fly! For the past 25 years, I’ve been a fan of the British magazine Dazed & Confused – we salute them for always having their finger on the pulse of global Youth Culture!

via Dazed Digital

Beyond the romantic lights of the Eiffel Tower, Parisian suburbs in the 80s were gripped by a dark race war. In December 1983, the political tides were turning. The government was technically left but the Front National, led by Jean-Marie Le Pen, had just had their biggest ever electoral breakthrough. Far-right thinking was creeping into the mainstream, and a xenophobic rhetoric was beginning to spur on inner-city violence, with immigrants becoming the scapegoat for economic issues. “Many young people who had immigrant parents, or had themselves immigrated suffered violence in the corridors of the metro or squarely in the street,” explains Michael Patrick Lanoh, a black student who had discovered new and troubling elements to the city.

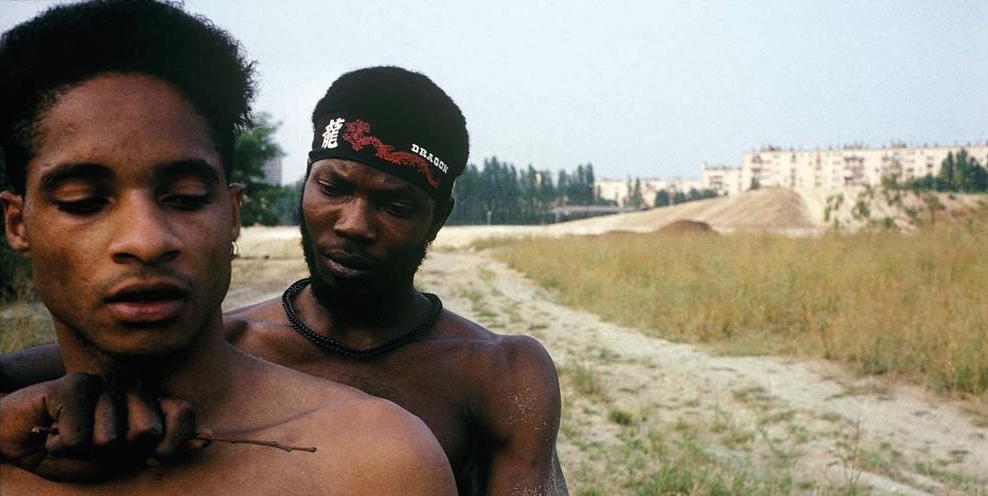

Often when militant black movements are discussed it is in direct reference to The Black Panther party in America. However, this overlooked era of black European history a violent clash of cultures that have since been forgotten. The city’s thriving nightlife saw the punk scene’s skinheads morph into fascist gangs who fought counter-fascist gangs on the Paris metro. And when punk became political, the Black Dragons gang was born – an all-black militant movement who vowed to fight back and hunt down fascists.

Courtesy of Michael Patrick Lanoh

Modelled on the likes of Patrice Lumumba, Malcolm X and the aforementioned Black Panthers, to whom they were self-proclaimed heirs, the group decided that combative backlash was the only way to survive. Aesthetically punk, politically left and partying at the dawn of hip-hop, they embodied the new multicultural society that radicalised youths were trying to erase. “We roamed the district of La Défense in Paris, dressed in all-black – black bombers, jeans and black lace-up Doc Martens, led by a Haitian named Yves Madichon who we called Yves le Vent,” he explains. At first, Black Dragons were mostly the sons of diplomats and senior African officials based in France for a predetermined period. Lanoh was one of the original members of the group who had been sent to France to study but became disgusted by the behaviour. He became radicalised when he and a few friends came under attack.

In his book I was a Black Dragon, Lanoh describes how skinheads tracked him and his friends down in a train carriage after they left school late one night and called him a “dirty n*gger” and his friend a “fucking Arab”. “We were attacked on the train home, they shoved us and we took some serious blows, luckily without too much damage,” he says. “But no-one in the car helped us. On leaving the train, my vision of the world had changed dramatically. I felt like I had entered into battle. I’d say that is the moment that I really became a Black Dragon.”

Chasing skinheads became a full-time operation. The athletic collective began practicing martial arts and combat sports four or five times a week to prepare for battle. Most of the violent clashes would take place in the underground corridors of the Paris metro. “Sometimes we would receive information on their movements and locations or we would make ourselves public on purpose to lure them to a park,” recalls Lanoh. “We always chased them home.” The militant leather jacket-clad group were decked out in black berets and wore the crest of a dragon on one shoulder and the American flag above the USSR flag on the other. A “hallmark of skinhead hunters”.

“We trained new Black Dragons to respond to provocations from those trying to attack us. We were young and revolted by what was happening around us. In transport, or when we were isolated and alone in public, we were the Skinheads prey,” he said of the group’s discipline. “The creation of our movement coincided with the arrival of hip hop in France. We grew up with this culture. Often we spent our evenings begging DJs to play our music, mostly rap and African music, especially Congolese. But we strictly prohibited any use of drugs or alcohol.” The punk aesthetic faded and they created a female arm for the movement. Miss Black Dragons were trained groups of girls who were already “Amazons” and “Snake-Girls” – independent groups who were not tied to anyone or a particular movement. They became an integral part of the movement – first, they helped with logistics but eventually fought alongside the men. Although a dangerous and unusual pastime, Lanoh said this was a way for black girls to rebel against the patriarchal norms of their upbringings. “Given that the African education system was a lot stricter for girls than for boys, Miss Black Dragons were a part of a generation of women who looked for emancipation in the streets.”

But they were met with disapproval from people in their own communities. “Our families did not accept our behaviour because of how young we were – we were only teenagers and we were fighting and going on nights out already.” In such stark contrast to normal adolescent activities back home – basically just studying – the newcomers quickly found that their legal guardians disapproved of their new pastime. Their families back home couldn’t quite grasp the pressures of living in a racist Western society so far away from home and in many ways didn’t understand racism at all. His mother began sending him furious letters after a photo of him appeared in a newspaper article about gang wars. However, united by their “arrogance” as Lanoh puts it, the movement expanded and grew stronger by recruiting in other neighbourhoods where several gang members joined. Soon the Black Dragons were made up of black Africans and Caribbeans all fighting for the same cause.

Courtesy of Michael Patrick Lanoh

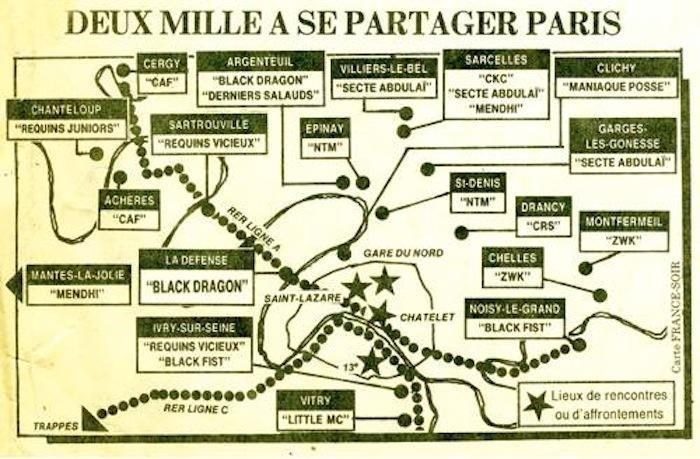

By the 90s, skinheads became increasingly rare in the streets of Paris. “We had grown up to 900 dragons, to the discontent of many. Inevitably, tensions grew between us and other Parisian gangs,” says Lanoh, noting that most of those tensions were related to parties and girls. “They allied against us and attacked us in our headquarters in what the newspapers called the “first gang war”. By then the media objected to us and other collectives like the “Junior Sharks”, or “The Black Fist”. Another large fight happened between the Junior Sharks, Mendy Force, the CKC, the Vicious Sharks and The Black Dragons. However, in-fighting between gangs that had the same philosophy of opposing the fascists eventually killed the movement.

Years later, Lanoh wrote a book documenting his time policing Paris’ streets. Despite his mother’s incessant worrying and disapproval, his father understood and Lanoh says his book was for him. “In my book, I compare my years in the gang to today I definitely think we can see similarities. The left is in power again, meanwhile extreme ideas prevail. Verbal violence towards foreigners was rare back then, when racist speech would only be expressed in private or in small groups. Now, the extreme-right parties are no longer demonised and their leaders are invited to TV broadcasts, their racist ideologies have become commonplace,” he says. “Modern-day skinheads don’t fight in the streets of Paris, they have opted for a jacket and tie so they blend better into society and quietly exercise their baneful influence.”