“If God existed, only in one way could he serve human liberty – by ceasing to exist.” – Mikhail Bakunin, God and the State

Claimed as “the greatest clerical bloodletting Europe has ever seen,”1 the early days of the Spanish Civil War saw nearly 7,000 members of the Catholic clergy systematically executed as hundreds of churches, convents and monasteries were burnt to the ground. Religious icons were profaned, the tombs of saints desecrated, and “public acts of unspeakable blasphemy” were performed to the approval of jubilant crowds.

While much of the outside world was shocked by the anti-religious “red terror” that swept over the country, in reality these iconoclastic acts were the culmination of nearly five hundred years of popular resent. The Catholic Church was seen by many as a fundamentally corrupt institution, which served the interests of the rich and powerful while keeping the poor in moral servitude. Militant anticlericalism became widespread,2 and with the revolutionary floodgates opened by civil war there was no holding back the popular fervor to “reclaim the soul of Spain” from this centuries-old theocratic grip.

THEOCRACY IS THE ESSENCE OF TYRANNY

“We live in such difficult times that it is dangerous either to speak or be silent.” – Juan Luis Vives, Valencian humanist philosopher, 1534

Since the Iberian Visagoths first converted to Christianity in the late sixth-century, the religion has played a central role in shaping the political landscape of the Spanish region. As the Moorish kingdoms in the south were conquered during the ‘Reconquista’ period, the power of the Holy Roman Church was consolidated throughout the Iberian peninsula. Indeed, the newly established Spanish kingdom was considered to be the perfect Christian State (“chosen by God”) because it was ruled by the most pure form of Catholicism in all of Europe.3 As can be expected, anticlerical attitudes were widespread among the heavily taxed and regulated lower classes, with hostilities periodically boiling over into violent acts of rebellion – often directed against Church property and officials.4

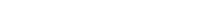

In 1478, the Tribunal del Santo Oficio de la Inquisición (aka ‘The Spanish Inquisition’) was established by the Catholic Monarchs Ferdinand II and Isabella I. This new institution replaced the Medieval Inquisition, which was under Roman Papal control, and enforced a strict nationalist Catholic orthodoxy across the recently unified Spanish kingdom. Unlike elsewhere in Europe, where the Inquisition operated relatively independent of the state, Spain was unique in how closely the machinery of religious terror was tied to the ruling monarchy, “merg[ing] itself into the existing power structures, and gain[ing] the collaboration of local elites, who were happy to accept honorary posts (as ‘familiars’) in the tribunal”.5 In time the Inquisition developed into something of a secret police force, tasked with the elimination of internal threats to the theocratic Spanish state.

In the eastern provinces of Catalonia, Aragon, and Valencia – where some of the heaviest concentrations of anticlerical violence would take place during the Spanish Civil War – the Inquisition was always a despised institution. In fact, the Catalan resistance became so widespread that fearful inquisitors complained: “In this province, they bear ill-will to the tribunal of the Holy Office and would destroy it if they could.” In 1574, an Inquisition official narrowly escaped lynching by the people of the Vall d’Aran, in the Catalan Pyrenees.6 And in neighboring Aragon, Father Pedro Arbues, the chief inquisitor of the kingdom, was stabbed to death at a cathedral altar as he knelt in prayer.7

However, on the whole, resistance proved futile. For over three-hundred years, the Spanish people was subjected to a nightmare existence of paranoia, censorship, persecution, imprisonment, torture and death. The main victims were Jews, followed by Muslims, Protestants, and “heretics” of various distinction. But the oppressive chill was felt throughout all levels of Spanish society, both in the public and private spheres: “No offense against moral order was too trivial to escape the attention of the Spanish Inquisition. A quarrel between congregants during a Sunday mass, a curse uttered during a game of dice, a flirtatious remark offered to a young woman during a religious procession, the eating of meat on a Friday, and the failure to attend church services were all the subject of inquisitional proceedings”.8

In addition to maintaining strict religious regimentation, the Inquisition was also a powerful tool of the Spanish monarchy for suppressing political opposition and public dissent – and in its later years, during the Catholic Counter Reformation, the vast inquisitional terror networks provided “anti-modernist” shock troops in the culture war against the Enlightenment values that were beginning to creep into the country. Any semblance of secular education, social and scientific progress, representative democracy, women’s rights, religious toleration or humanist ideals was ruthlessly crushed under the foot of harsh Catholic traditionalism.9

Spain’s long nightmare came to an end in 1834, when the institution was formally abolished by royal decree. It’s estimated that as many as 30,000 people were executed during the Spanish Inquisition. Another 17,000 people were burned in effigy, and nearly 300,000 “penanced” in various other ways.10 The psychological scars left behind by this dark chapter in Spanish history ran deep, and would not be soon forgotten.

FEAR GIVES WAY TO ANGER

“Being a priest or a monk is all that is required in order to rape and kill almost with impunity.” – Rodrigo Soriano, deputy from the republican Radical Party

The Spanish Inquisition was formally abolished in 1834, its final years marked by violent challenges from a newly emboldened populace. Throughout the 18th century, disputes over rent and tax collection led to regular outbursts and occasional uprisings in the rural areas of the country. This natural peasant antagonism towards the Church (who often acted as both landlord and local authority) would find coherence in the anticlerical ideas that flooded into the country during the Napoleonic invasions of 1808-14.11

When the liberal revolution of 1820 broke out, the Catholic Church was temporarily stripped of many of its privileges. A wave of popular anticlericalism swept through the streets as urban mobs chanted “Death To The Friars!” and attacked religious institutions. In response, monks and priests began organizing guerrilla bands to carry out terrorist attacks against the new regime.12 Over a decade later, social tensions unleashed by the First Carlist War exploded in a new round of anticlerical mob violence. During the summer of 1834, crowds of people stoned monasteries in Barcelona during public demonstrations13 and rioting mobs left seventy-eight Jesuits, Franciscans, Dominicans, and Mercedarians dead and their residences destroyed in Madrid.14

In one deadly incident, an angry mob shouted blasphemies as they stormed the Saint Ignatius Seminary: “When the young Father Sauri opened the door, demanding to know what they wanted, someone in the mob shouted “We want your blood, dog!” The furious crowd entered the huge building and hunted down the occupants one by one. Father Sauri was stabbed by men, mutilated by women, and dragged by children to the Plaza de San Millán.”15

Spain’s Catholic oligarchy had been left shaken by the mob violence and liberal secularizing attempts of the mid-nineteenth century, but in 1874 it once again enjoyed institutional protection under the corrupt Restoration Monarchy: “The Church relied on the regime – whose formal constitutionalism belied the violent mistreatment which Spain’s rural and urban poor endured at the hands of the state security forces – in order to defend and augment its political, economic and cultural power. In these circumstances, religious personnel became the guarantors of a rigidly hierarchical social and cultural order. Correspondingly, many workers [saw] the institution as the brutal ideological backbone of a political system which excluded and oppressed them, and as the ally of a state which intruded with growing intensity into their private lives.”16

It was during this period that a militant, almost apocalyptic, form of anarchism began to take hold among large sections of the urban working class and landless rural peasantry – further radicalizing the already popular culture of anticlericalism among Spain’s poor. Both Church and State were considered to be “one single tyranny… the leeching mouth of a vampire which lives off the blood of the people” that needed to be violently overthrown, and from this purifying catharsis of revolution a free and egalitarian future society would be born.17

It wouldn’t take long before the fiery anticlerical rhetoric of the anarchists was backed by militant deeds.

THE BATTLE LINES ARE DRAWN

“It is clear that nowadays hatred toward the Church runs deeper than hatred towards capitalism.” – Canon Maximiliano Arboleya, social-liberal Catholic leader, quoted during the Asturias Uprising, October 1934

In 1896, a bomb was tossed at the Corpus Christi Day procession in Barcelona on Easter Sunday, killing six people and seriously wounding another forty-five.18 In the aftermath of the bombing, martial law was declared and a period of severe repression swept over Spain as hundreds of anarchists, labor activists and radical sympathizers were jailed and brutally tortured in the Montjuich fortress. As news of these tortures spread, anticlerical riots broke out in Cadiz, Saragossa, Valencia and other towns.19 This bitter animosity continued as large anticlerical demonstrations took place against the Jubilee of Christ the Redeemer celebrations around the country in 1901. Catholic processions were disrupted by protesters armed with clubs, and the windows of churches, convents, Catholic schools and seminaries were smashed.20

In July 1909, a week of draft riots broke out in Barcelona following the forced enlistment of reserve units to fight in the North African colonies. Angry mobs implicated the Church alongside the political elites and attacked religious institutions. Nearly half of the city’s church buildings were burned, tombs and religious icons were profaned, and three priests were killed.21 Commonly referred to as “The Tragic Week” (and “The Week of Glory” by the radical press of the time), “the streets of Barcelona hosted a clash between two different outlooks on life: on one side, the old world, the Church, classist education, the old order, what progressives called “superstition”; and, on the opposite side of the barricades, the anarchist idea, free thought, the emerging status and independence of women, secularism, reason and Darwinism.”22

The next decade was one of violent class conflict, marked by regular cycles of resistance and repression. Amidst this antagonistic social backdrop, the Catholic clergy sided directly with ruling class interests, often providing strikebreakers when needed and even organizing some of the right-wing terror squads that operated in the countryside (Juan Soldevilla y Romero, the ultra-reactionary Cardinal Archbishop of Saragossa, was murdered by anarchists in revenge for his role in financing and recruiting assassins to gun down union organizers during this period23).

This general state of lawlessness lead to the military coup of General Miguel Primo de Rivera in September 1923. Martial law was declared, the constitution suspended, labor unions suppressed, political opponents jailed, and a strict system of censorship was imposed. The coup was backed by King Alfonso XIII and his “traditionalist” supporters in the military and Catholic Church – establishing an alliance that would unite with other fascist and reactionary forces under Francisco Franco during the Spanish Civil War.24 The dictatorship lasted until January 1930, when the unpopular Primo de Rivera was asked to step down by the king who hoped to reestablish political normality under a constitutional monarchy.

National elections were soon held and the Second Spanish Republic was established on April 14, 1931. A new era of social, political and economic modernization had begun, and to affirm this climate of progressive change, Manuel Azaña Díaz, the left-Republican prime minister, declared in his first public speech that “Spain has ceased to be Catholic!” to roaring applause.25 For republican reformers, “the powerful, doctrinally and politically ultra-conservative Spanish Catholic Church was the principal obstacle to modernization, [and they] made clear their intention to take secularizing measures to limit the Church’s economic strength and political influence, and to break its cultural power.”26 An alarmed Cardinal Pedro Segura, the Primate of Spain, responded by urging Catholics to vote against the new republican government in all future elections and to support the far-right opposition “in defense of the Church”. The battle lines had been reaffirmed, and as Catholic forces were being mobilized against the Republic, popular anticlerical attitudes were being hardened. All that was needed was a spark to ignite the country’s resent in explosive violence.

That spark was provided when provocateurs played monarchist anthems in the streets of Madrid to protest the new republic. In response, widespread rioting broke out for three days and, once again, the Church became a focal point for popular anger. As the social unrest spread across Spain, hundreds of convents, churches, Catholic schools and other religious buildings were torched – an event infamously known as “La Quema de Conventos” (The Burning of the Convents).27

Despite the progressive reforms and concessions made by the new Republican government, the political landscape of Spain was radically polarized during this period – with challenges from both the far Left and Right. The situation only got worse after the 1933 electoral victories for a number of ultra-conservative obstructionists, who now controlled nearly half the parliamentary seats. A series of labor strikes spread across the country, and the province of Asturias erupted in open insurrection the following year. Police and army barracks were raided as armed miners took control of a number of towns in what was dubbed as “The Asturias Uprising”.28 It wouldn’t take long for old scores to be settled in these newly liberated areas: thirty-four priests, seminarians and brothers from the Escuclas Cristianas in Turón, Granada, were executed. Additionally, fifty-eight churches, the bishop’s palace, a seminary, and the Cámara Santa cathedral in Oviedo were all either blown up or burnt to the ground. The level of ferocity against the Church hadn’t reached this level since the anticlerical riots of a hundred years earlier.29

The uprising was eventually put down, with 3,000 miners killed and another 35,000 taken prisoner (in many cases the prisons and holding centers were religious buildings, such as the Adoration Sisters’ convent in Oviedo and others in Sama and Ciano30) during the wave of repression that followed. Attempts were made to restore public order in Spain, but the gears of civil war were already motion.

CHURCHES BURN AS THE NATION BLEEDS

“We have rounded up all the priests and parasites… we have lit our torches and applied the purifying fire to all the churches… and we have covered the countryside and purified it of the plague of religion.” – Solidaridad Obrera, anarchist newspaper, August 20, 1936

On July 17, 1936, General Francisco Franco launched a fascist coup against the democratically elected Republican government. The coup was met by the combined resistance of government forces still loyal to the Republic and armed anarchist and socialist workers who put down Francoist forces in Madrid, Barcelona, Valencia, Bilbao, and Málaga. The country was fractured and divided in its support, descending into a bloody three-year civil war that would devastate Spain and claim hundreds of thousands of lives.

Beyond the right-wing military units and ultra-conservative political groups who joined his coup, Franco also had the strong backing of the Catholic Church. Priests preached hatred against “the reds” from their pulpits, blessed Franco’s troops and some even adopted the fascist salute. In a public declaration, Enrique Pla y Deniel, the Bishop of Salamanca, referred to the military uprising as “a Crusade against the children of Cain… a Crusade for religion, for the fatherland, for civilization”.31

The feelings were mutual, and with war declared there was no holding back the bitter feelings towards the Church held by the thousands of radicalized workers who took to the streets – and were now armed. Following the failed Francoist rebellion attempts in Republican stronghold areas, members of local militias methodically executed clergy members and destroyed church property.

The wave of clergy killings touched off by the civil war was staggering, even by Spanish standards. According to the most accurate estimates, 6,832 members of the Catholic Church were killed during the Spanish Civil War, a majority during the first two months of fighting. This included 13 bishops, 4,172 diocesan priests and seminarians, 2,364 monks and friars, and 283 nuns.32 The majority of these killings were collective in nature, with groups of clergy members rounded up and publicly executed. This wasn’t just a matter of personal prejudice or revenge, but a passionate expression of social revolutionary vengeance inspired by centuries of hatred towards the Church. In fact, these feelings were so extreme that even after death the bodies of clergy members were subjected to public mockery and mutilation, or else dragged through the streets. In one example, “[the] parish priest’s body was ‘shamefully mutilated,’ dragged through the city [of Murcia] and finally hoisted up the bell tower of his own church, where it went up in flames with the rest of the building.”33

Given the frenzied nature of the anti-religious mob violence (which at times included overt sexual transgressions, such as the public stripping and mockery – and in extreme cases, castration – of priests), it is interesting to note that there is not one single documented instance of rape perpetrated against any nuns during this period. In a report from Madrid’s Diocesan Archive on the civil war experiences of Ciempozuelos’ Oblate nuns: “Though the nuns were threatened frequently by the committee and the militiamen, they were not molested physically at all.” In fact, across the entire republican zone, ninety-seven percent of the victims of anticlerical violence were men.34

However, morality only went so far in this emotionally charged social climate. Swept up by anticlerical passions, acts of desecration soon became more and more extreme. In a carnivalesque celebration of the macabre, tombs were opened and church graveyards dug up as the remains of saints, priests, and nuns were exhumed and profaned in the streets of Barcelona, Madrid, Toledo, Valencia, and Almeria. In the famous Romanesque monastery of Ripoll, “the sepulchers [were] destroyed, among them that of Wilfredo el Velloso, the conqueror of Catalonia, and that of Bishop Morgades, the restorer of the famous abbey. In Vich, the tomb of the great Balmes was profaned, and people have played football with the skull of the great Bishop Torras y Bagés.”35 Further incidents took place in Toledo, at the Church of San Miguel, where disinterred corpses were displayed on the central altar, and Madrid, where skulls were placed on the altar of Carmelite Church. In the most notorious incident, the bodies of nineteen Silesian nuns were exhumed and exhibited in Barcelona, “flanking the doors of the church and spilling out onto the street. Here they remained for three days, during which time more than forty thousand people filed past them, sometimes silent but more often jeering.”36

These acts of postmortem desecration, as bizarre as they seem, were considered by anticlerical participants to be “a bold defiance of religious taboos” that challenged the power of the Church and “exposed the mystery and occult forces of Catholicism as powerless in the face of irreligious attack.”37

In addition to widespread violence against religious personnel, both living and dead, there was also a systematic campaign of destruction against church property unleashed by the revolutionary fervor. Churches were set ablaze, shrines were defaced, statues destroyed, treasures looted, and religious art became kindling for the nightly bonfires. This ritual destruction was seen as an assault on the public presence of Catholicism and the emotional power it still held over the population. According to Father Antonio Montero Moreno, in his study of religious persecution during the Spanish Civil War, it was this material destruction of ‘the sacred’ that unveiled “a rage against the religious world far more significant than if the killed are men of flesh and bone.”38

After the dust had settled, it had been estimated that 150 churches and cathedrals were completely devastated during this period, with another 4,850 severely damaged (of which 1,850 were considered “more than half destroyed”).39 In a euphoric report from the Republican front lines, the anarchist newspaper Solidaridad Obrera proclaimed: “Catholic dens no longer exist. The people’s torches have reduced them to ashes. In their place, a free spirit will be born, which will have nothing to do with the masochism that was nurtured in cathedrals.”40

A typical church burning during the early days of the Spanish Civil War is described: “On August 10, 1936, […] a crowd of 200 to 300 leftist radicals gathered in front of Aracena’s [in Andalusia] 16th century parish church of Santa Maria de la Asunción. [They] entered the sanctuary and began to strip the walls, altars, chapels, and treasuries of their images, paintings, chalices, crucifixes, and other furnishings. […] All of these objects were gathered into a great pile in the center of the church and set ablaze. As the flames rose, dynamite charges exploded. Although the weakened stone walls did not collapse, the whole edifice was gutted. In succession, the other churches and chapels of the town met the same fate.”41

The burning of churches provided an ideal means for the newly empowered lower classes to intimidate the conservative gentry and demonstrate their control over the town, particularly in rural areas. For generations the local elites had donated the paintings, images and other furnishings to local churches, and thought of themselves as the patrons and guardians of these artistic treasures. To sack these “houses of the rich” and destroy the most visible representation of the ruling class’s cultural and political values was a humiliating act, demonstrating vulnerability and impotence, which served as a powerful form of psychological warfare.42

Churches that weren’t completely destroyed were gutted of Catholic symbols and transformed into political headquarters, schools, theaters, popular kitchens, barracks and hospitals.43 Even confessional booths found new and creative uses, as militiamen moved the cubicles “which once collected whispered secrets” from churches to central plazas and other public places. The booths were used as sentry boxes, newspaper kiosks, and – in the instance of the confessional booth taken from Madrid’s Convent of the Sacred Hearts – a hen house.44

Other symbols of the Catholic faith were also publicly attacked by the anticlerical mobs. Statues and plaques dedicated to the ‘Sacred Heart of Jesus’ in particular had long been an object of hatred for Spaniards. The Cult of the Sacred Heart goes back to the time of Bernardo Francisco de Hoyos, the Jesuit priest who claimed to have a vision in 1733 where Christ declared: “I shall reign in Spain and with more reverence than elsewhere.” The mythos of the Sacred Heart became popular among Catholic absolutists, symbolizing this “great promise” of a totalitarian Christian State in Spain.45 In the days following the outbreak of civil war, the colossal Sacred Heart of Jesus statue in Aranjuez, just outside of Madrid, was torn down using ropes and a mule-cart. When the statue hit the ground and shattered, the head was seized and thrown into the river. In Almeria, local militiamen blew up the Sacred Heart monument in the town square. Elsewhere in Spain, images of the Sacred Heart were burned, smashed with pickaxes, hurled from balconies and publicly ‘executed’ by firing squad.46

Public blasphemy and mock religious events took place in the Republican controlled areas as well. In the town of Ciempozuelos, near Madrid, right-wing sympathizers were forced to march in “Catholic procession” while armed revolutionaries, dressed in priestly robes, sang obscene parodies of religious hymns on the feast day of Our Lady of Consolation.47 There was also reportedly mock weddings performed in Ciudad Real with the city’s prostitutes, followed by mock processions with all their sacred trappings. In Alcañiz, a town famous for its Holy Week events, people organized a parody Lamentation of Christ procession. And in Calanda, a group of local elites were forced to carry the image of the Virgin of the Column through jeering crowds to the town’s bullring, where it was destroyed.48

As the revolution progressed, militant secularization efforts advanced throughout the liberated areas and swept aside anything associated with the Church: “Anything – whether institutions, streets, villages or geographical features – named after a priest or saint was apt to be renamed: in Catalonia alone, more than 100 villages whose names began with “Sant” or “Santa” were renamed. […] One could not even say goodbye using the conventional expression adiós (“with God”), since the revolutionaries corrected anyone adhering to old habits by reminding them that ‘there was no more God in heaven’.”49

CONCLUSION

Spain eventually fell to Franco’s Nationalist alliance (which was backed by the German Nazis, Italian fascists and the Holy Roman Catholic Church by the end of the war) when the last of the Republican forces surrendered on April 1, 1939. Pope Pius XII was one of the first to send the victorious Franco a congratulatory message. In it he singled Spain out as “a nation historically chosen by God to spread the message to the New World and as an invincible bulwark of the faith,” which provided “the clearest proof that, above everything else, the eternal values of religion and the soul still survive.”50 With the blessing of the Church, over 50,000 people would be rounded up and executed under Franco’s “White Terror” campaign between 1939-1946 (with many more imprisoned or sent into exile).51 A new Spanish Inquisition had begun.

In the aftermath, “churches and public spaces all over Spain were filled with commemorations of the victors, with memorial plaques for those who had “fallen for God and for the Fatherland,” while a veil was cast over the ‘cleansing’ in the name of God carried out by the pious and people of order.” The memory of murdered religious martyrs enhanced the Church’s influence, “and by doing so, eliminated the last vestiges of sympathy for the vanquished that there might have been, heightening the clergy’s thirst for revenge for many years to come.”52

But for a brief moment in Spanish history, the reactionary grip of the Catholic Church was broken in large areas of the country and the mystique of religion shattered by the cathartic violence of anticlerical militants. It was a true iconoclasm, in every sense of the word, “since not only did it entail the actual annihilation of the clergy, of temples and devotional objects, but also through the destruction of holy ‘icons’ – whether living icons such as priests and clerics, or inanimate ones such as paintings and statues – unbelievers proved to believers (and themselves) the impotence of the Catholic God, his idols and representatives and the very non-existence of the sacred sphere.”53

Mark Laskey

http://illuminating-shadows.blogspot.com

——–

FOOTNOTES

1. Jose M.Sànchez, The Spanish Civil War as Religious Tragedy (Notre Dame, IN: University of Norte Dame Press, 1987), 8.

2. Roderick Kedward, The Anarchists: The Men Who Shocked an Era (Winter Park, FL: American Heritage Press, 1971), 68.

3. James Maxwell Anderson, Daily Life During the Spanish Inquisition (Westport, CT: Greenwood Publishing, 2002), 47.

4. Maria Thomas. “The Faith and the Fury: The Construction of Anticlerical Collective Identities in Spain,1874–1931,” European History Quarterly, vol. 43 no. 1 (January 2013): 75.

5. Henry Kamen, The Spanish Inquisition: A Historical Revision (New Haven: Yale University Press, 1999), 81.

6. Kamen, 81-82.

7. Joseph Pérez, The Spanish Inquisition: A History (New Haven: Yale University Press, 2006), 33.

8. Jonathan Kirsch, The Grand Inquisitor’s Manual: A History of Terror in the Name of God (San Francisco: HarperOne, 2009), 187-188.

9. Kirsch, 186.

10. Kirsch, 202.

11. Timothy Mitchell, Betrayal of the Innocents: Desire, Power, and the Catholic Church in Spain (Philadelphia: University of Pennsylvania Press, 1998), 32.

12. Mitchell, 33.

13. Adrian Shubert, Social History of Modern Spain (London: Routledge, 1990), 164.

14. Patrick Foley, “But What About the Faith? Catholicism and Liberalism in Nineteenth-Century Spain,” Faith & Reason: The Journal of Christendom College, Vol. XVI, No. 4 (Winter 1990).

15. Mitchell, 34-35.

16. Thomas, 76.

17. Thomas, 85.

18. Mitchell, 41.

19. Julio De La Cueva, Culture Wars: Secular-Catholic Conflict in Nineteenth-Century Europe (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2009), 193.

20. Eric Storm, Political Religion Beyond Totalitarianism: The Sacralization of Politics in the Age of Democracy (Basingstoke, UK: Palgrave MacMillan, 2013), 240.

21. John Coverdale, Uncommon Faith: The Early Years of Opus Dei, 1928-1943 (Strongsville, OH: Scepter Publishers, 2002), 78-79.

22. Dolors Marín Silvestre, “Barcelona July 1909: A City in Flames, Tragic Week and the Murder of Ferrer i Guardia,” Kate Sharpley Library, https://www.katesharpleylibrary.net/n8pm38.

23. Abel Paz, Durruti in the Spanish Revolution (San Francisco: AK Press, 2006), 138.

24. Maria Thomas, “Disputing the Public Sphere: Anticlerical Violence, Conflict and the Sacred Heart of Jesus, April 1931-July 1936,” Cuadernos de Historia Contemporánea, 33 (2011): 49-69.

25. Stanley Payne, Spanish Catholicism: An Historical Overview (Madison: University of Wisconsin, 1984), 155.

26 Thomas, 73-74.

27 Hilari Raguer, Gunpowder and Incense: The Catholic Church and the Spanish Civil War (London: Routledge, 2007), 25.

28. José Luis Mulas Hernandez, “The Asturian Commune of 1934,” Kate Sharpley Library, https://www.katesharpleylibrary.net/4f4rh2.

29. Julian Casanova, The Spanish Republic and Civil War (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2010), 108.

30. Julio Reyero, “The Church and Anti-Clericalism in 20th Century Revolutionary Processes in Spain,” from Iglesia y anticlericalismo en los procesos revolucionarios del siglo XX en España (Madrid: Publicaciones El Sembrador, 2012).

31. Daniel Sueiro, Historia del Franquismo (Madrid: Argos Vergara, 1985), 71.

32. Julio de la Cueva, “Religious Persecution, Anticlerical Tradition and Revolution: On Atrocities against the Clergy during the Spanish Civil War,” Journal of Contemporary History, Volume 33, Number 3: 355.

33. Mary Vincent, The Splintering of Spain: Cultural History and the Spanish Civil War, 1936-1939 (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2011), 78.

34. Maria Thomas, “Masculinity, Sexuality and Anticlerical Violence during the Spanish Civil War,” PhD diss, Royal Holloway University of London, 2011.

35. “Joint Letter of the Spanish Bishops to the Bishops of the Whole World Concerning the War in Spain, July 1,1937,” War In Spain (New York: America Press, 1937).

36. Bruce Lincoln, Discourse and the Construction of Society (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 1992), 106.

37. Kedward, 68.

38. Vicente Sánchez-Biosca, “Killing God, Executing Christ: Modern Weapons for Old Dreams,” paper presented at the King Juan Carlos I Center, New York University, February 26, 2013.

39. Hugh Thomas, The Spanish Civil War (New York: Modern Library, 2001), 606.

40. “Catholic Dens No Longer Exist,” Solidaridad Obrera, August 20, 1936.

41. Richard Maddox, “Revolutionary Anticlericalism and Hegemonic Processes in an Andalusian Town, August 1936,” American Ethnologist, Vol. 22, No. 1: 125.

42. Maddox, 130.

43. Thomas, “Disputing the Public Sphere.”

44. Thomas, “Masculinity, Sexuality and Anticlerical Violence.”

45. Sánchez-Biosca.

46. Thomas, “Disputing the Public Sphere.”

47. de la Cueva, 362.

48. Julián Casanova, A Short History of the Spanish Civil War (New York: I. B. Tauris, 2014), 74.

49. de la Cueva, 363.

50. Sueiro, 81.

51. Casanova, A Short History of the Spanish Civil War, 187.

52. Casanova, A Short History of the Spanish Civil War, 79-80.

53. de la Cueva, 365.