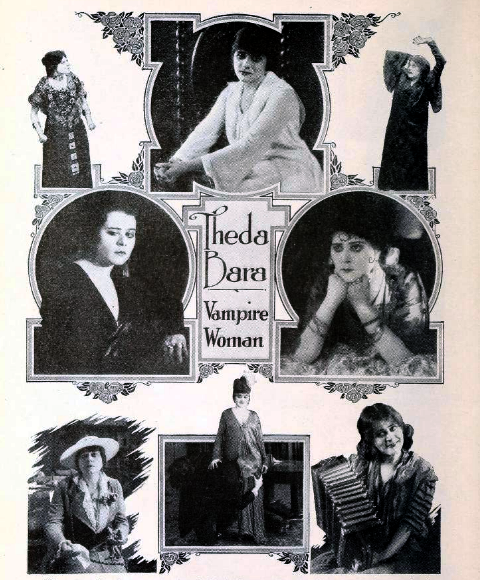

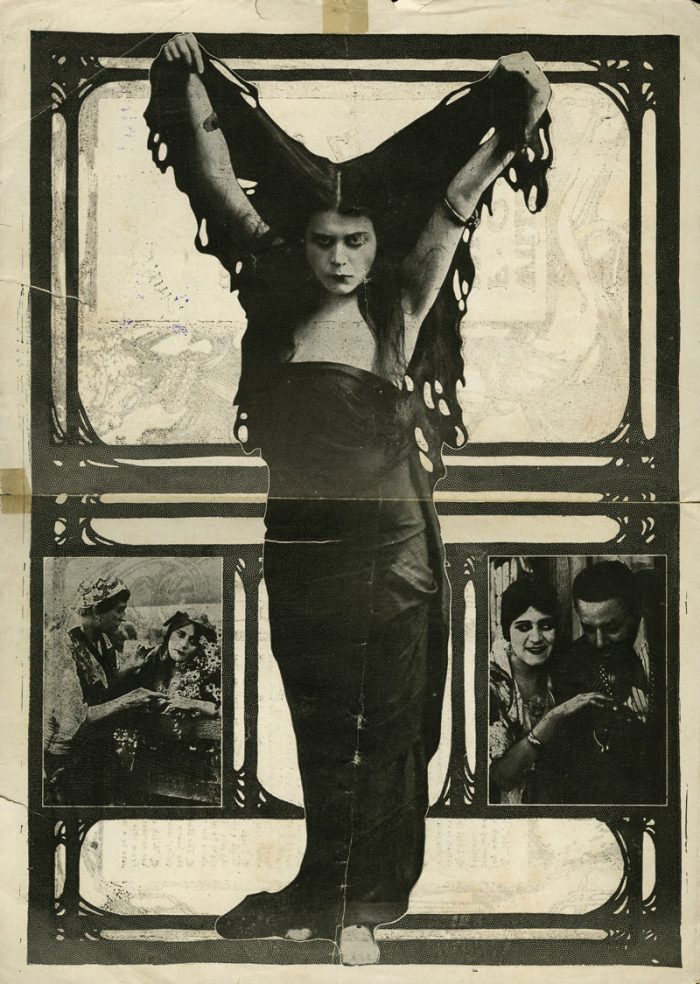

In January, 1915, much of America was still lit by gaslight; women did not yet have the right to vote, and the First World War was in its early stages; Edwardian sensibilities and fashions ruled the day, as witnessed by the reigning “Gibson Girl” notion of ideal femininity; and in dark moving-picture exhibition houses that served as the stations of a nascent motion picture industry whose cultural influence no one could then predict – an alabaster-skinned woman with dark, raccoon eyes and funereal attire captivated audiences as “The Vampire” in A Fool There Was – Theda Bara.

Theda Bara was the first mass American sex symbol. She started her motion picture career in earnest in January, 1915, when Fox Films’ A Fool There Was took America by storm (She did have a small role as an extra in 1914’s The Stain). In 1916, The New York Times estimated that “in a day 440,000 persons see Miss Bara in the films” and that her fan letters “average more than 100 daily, and one day recently the postman brought 205.” A year later, magazines would report she received around 400 letters per day.

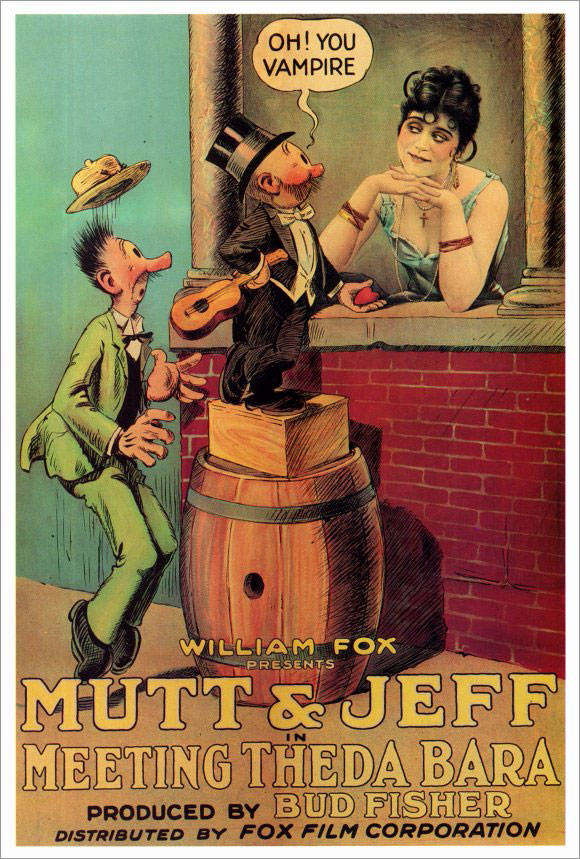

Theda’s “vampire” character in A Fool There Was ushered in the word – and idea – of the vamp. Two years later, in 1917, she played the title role in one of the great lost films of motion picture history, Cleopatra (Of course, 2017 is the centennial of that movie). By 1920, Theda Bara’s motion picture career was mostly over.

Theda’s relatively short time in films belies her incredible productivity while working, however. She made about one movie every six weeks while working for the Fox Film Corporation in the mid- and late-1910s, for a total of about forty four films (She made two film appearances in the 1920s). Tragically, ninety percent of these are now lost, victims of a 1937 Fox film vault fire, inadequate movie preservation methods, and the naturally combustible and fragile nature of early nitrate film stock. Overall, 70% of American silent films are lost.

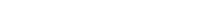

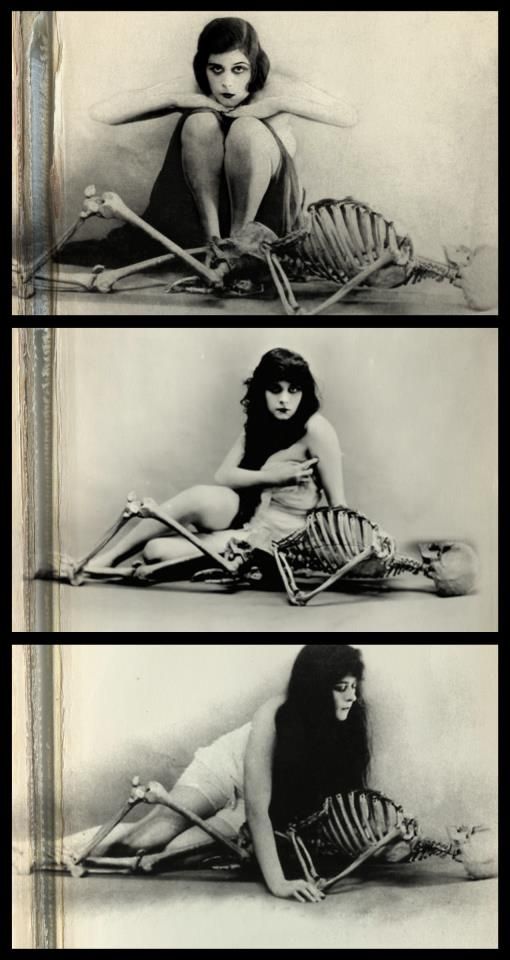

Until the late 1990s, no book-length biographies had been written about Theda Bara. It was notoriously difficult for writers to disentangle the facts of her life from the wild tales spun by Fox’s highly imaginative publicity department, and new things about Theda Bara are being discovered all the time. In 1915, Fox publicists hoped to thrill audiences by painting their new star as a soul-stealing, pleasure-seeking, cold-hearted succubus. The persona and mystique that they created for Theda Bara – and which Theda herself played along with for several years – paved the way for the Hollywood femme fatale tradition. Of course, Theda Bara’s characters were only metaphorically vampiric – just as in Rudyard Kipling’s 1899 “The Vampire” poem, upon which her breakthrough role in A Fool There Was was based – but through interviews and press releases Fox (and even Theda Bara herself) hinted that she might be in possession of eerie, otherworldly powers. Ultimately, Theda Bara’s vamp persona ended up having resonance even in the horror field, especially when it came to how future vampires of the undead sort appeared on screen: ghostly white skin, flowing raven tresses, kohl-limned eyes, and a hypnotic, alluring gaze became conventions of the character type. (This type of cinematic depiction for the undead had by no means been decided by the 1910s; the depiction of vampires as rat-like, Nosferatu-type creatures, or as shambling, decaying ghouls – these were also possible futures for the look of cinema’s undead at that time). The idea of a supernatural vampire versus an earthly home-wrecking vamp were often willfully conflated in press releases about Theda.

“Have the physical attributes of scheming Delilah, of cruel Lucretia Borgia, or of diabolical Elizabeth Bathory fatefully found reincarnation that the women of this age may see face to face the loathsome depths to which the worst of their sex have descended?” Fox publicists Al Selig and John Goldfrap breathlessly and rhetorically asked in a press released reproduced by many papers in 1915. “Are the souls of those monsters of ancient and medieval times welded with others to form the soul of Mlle. Theda Bara, the moving picture actress known as the most wicked-faced woman in the world?”

“Her kiss is death; her love red flame that scorches like a white hot brand; / but luring lightning in her eyes beckons to that forbidden land / where blasted lives, like hollow skulls, lie whitening on the sun-bit sand. / The vampire woman takes cruel toll, her blood-red lips are smiling lies that lull her fools in her white arms, and mock them in their parting breath, / and laugh to see their fell work done, as, cursing, gulls do down to death.” – Fox publicity copy from the Theda Bara film Devil’s Daughter

Fox created an origin story for their star: she was the exotic daughter of European artists or Arabian royalty (or some combination of both), was born in the shadow of the Sphinx in Egypt, was imbued with frightening occult powers, and had been a mesmerizing theatrical figure in the Grand Guignol and Theatre Antoine of Paris. She had come to America from France to escape the oncoming German onslaught in the nascent Great War. Of course, none of this was true. Some of the movie press played along, especially the writers that were fans of Theda (like, say, at Picture-Play); other, more cynical writers poked fun at Fox’s publicity department for their over-the-top hype. Just who was this woman, really?

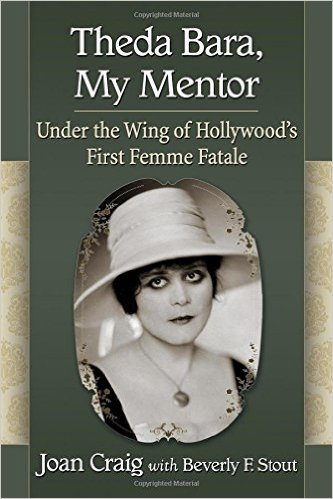

And that gets us to the book in question – Theda Bara, My Mentor: Under the Wing of Hollywood’s First Femme Fatale. The Fox-produced tangle of stories about Theda Bara and the confusion they created among subsequent writers is partially why Joan Craig and Beverly Stout’s new book is a welcome addition to the literature about the queen of cinematic vamps. Last Summer, their combined effort hit store shelves. The book is partially a biography of the famous film enchantress, but is also a memoir of Joan Craig’s childhood and her experiences growing up around Theda Bara during the actress’ later years. There are 107 photos included, and these run the gamut of covering all phases of Theda Bara’s career, as well as moments related to author Joan Craig’s childhood, a childhood that dovetailed with Theda’s life. Playing against type (as it were), Theda assumed an auntly, mentoring role to the young Joan. In the book, she describes her first meeting with the silent film legend, who was, by coincidence, also her neighbor:

A small woman appeared. She stepped forward towards me and stood for a moment. I went forward immediately to shake her hand and curtsied. As I looked up she seemed to have a golden aura around her with the most haunting, penetrating brown eyes and a very sweet smile. There was something magical about her. She gestured with her left hand and said, “Please sit here, and I will sit here on the couch.” […] Theda then said, “My name is Theda [pronounced Thayda]; however sometimes I am called Theda [pronounced Theeda].”

Theda would console Joan during times of crisis or after the death of her grandfather, often consulting a crystal ball that was used in another of her great lost films, 1918’s Salome. At one point, according to the book, Theda Bara and her husband, director Charles Brabin, even offered to adopt Joan from her parents. (“My parents’ response was that I could not go over [to Theda Bara’s house] for awhile,” Craig dryly writes.) Particularly humorous in the book are Theda Bara’s tongue-in-cheek references to her own vamp background:

“Would you like to know where I was born?” Theda asked. I nodded. She stood and I followed as she walked towards the lanai. Dramatically she said, “I was born under the shadow of the Sphinx. I was the child of a princess. My father was an artist.” She paused for a moment and held up her stuffed snake. “I was weaned on serpent’s blood.” Uncle Charlie [Brabin], who was following us, could hardly keep from laughing. As we walked into the lanai, I could see that in the middle of the floor lay a mummy. All around the room was pictures of a sphinx, the desert, pyramids and camels. […] Theda pointed to a picture of a tent as she said, “I lived in a tent in the middle of the desert in Egypt.” Then she pointed to the map of Egypt. I could imagine how hot it must have been. She leaned against the door with her arm draped over her head and said, “I can’t say any more!”

Craig’s book provides a valuable service in illuminating Theda’s home life after her retirement from films in the 1920s. Although Theda often hinted at a comeback and promised an autobiography, neither of these materialized, and writers have found Theda’s post-film years frustratingly hard to cover. Craig’s book remedies a lot of that. Joan Craig’s childhood with the Brabin/Bara family introduced her to a circle of Hollywood friends and activities that are fascinating to read about in and of themselves, including meeting with actors during the McCarthyite/Hollywood Blacklist era, among many other occasions. A party at aunt Theda’s house with a young Liza Minelli or Geraldine Chaplin (daughter of Charles Chaplin) was not unusual. As well, Craig’s book covers the tragically aborted biopic of Theda Bara that was to come out in 1950, and which would have starred Betty Hutton as the famous vampiress. It’s doubly unfortunate this project never got off the ground; it would have included recreations of scenes from Theda Bara’s lost 1910s movies, and Theda Bara and Charles Brabin were intensely involved in helping the movie along.

As mentioned above, Theda Bara was the star – and starring attraction – of one of the great lost films in motion picture history: 1917’s Cleopatra. In an era where publicly showing ankles was racy, the controversial epic silent film saw Theda Bara bare more skin than some Americans were comfortable with (This prompted a lot of puns in the press about “Theda Bare-a”). The movie famously caused protests and led to cuts from censors. Theda Bara herself sued one of the major censors of the day to get the film shown. Cleopatra resulted in record box office sales for the Fox Film Corporation, and helped build Fox into the juggernaut it later became, and is now (For better or worse!).

[youtube id=”rjbzCcAzSSo”]

“Theda Bara’s following is well known. Her ability to make hideous faces that are supposed to show a soul steeped in the deepest dyes of hell, and to show the loggy passion that stands for emotion carried to the final stress of absolute abandonment, do make a strong appeal to many, many spectators. While the picture [“Gold and the Woman”] was on at the Academy of Music I overheard one of two women near me say: ‘Yes, but she is good.’ The remark showed a prevalent opinion. This actress’ work is considered ‘good.'” – Hanford C. Judson, review of “Gold and the Woman,” Motion Picture World, April 1, 1916

“I never let the thought out of my mind that she was a pagan, not a Christian woman … but I must confess to being shocked at the movements and few clothes worn by the actress. She certainly was Hooverizing on clothes.” – Mrs. Benjamin Baker of the Better Film Committee of the Women’s Club of Omaha, 1917, a local film censorship organization

Theda’s vampire persona luxuriated in wickedness, smoking casually on long stemmed cigarettes while reclining languidly on a chaise lounge, delighting in her mastery over men. At least one French movie magazine cited Theda Bara as moviedom’s first dominatrix. Fellow silent film legend Mary Pickford wrote, “After Theda Bara appeared in A Fool There Was, a vampire wave surged over the country. Women appeared in vampire gowns, pendant earrings, and even young girls were attempting to change from frank, open-eyed ingenues to the almond-eyed, carmine-lipped woman of subtlety and mystery.” In 1978’s Virgins, Vamps, and Flappers, Sumiko Higashi wrote, “The attraction of [Theda Bara’s] Vampire lay precisely in her ability to paralyze the male until he was left completely without will…. The desire to surrender to a sexually dominating woman was a negation of self and the resulting loss of control viewed as a spiraling descent into confusion, darkness, and death.”

When Cleopatra came out, giving women the federal right to vote was still a hotly debated topic. In 1917 Theda told a reporter, “Cleopatra, the transcendent mother of all sirens, was animated solely by the urge for authority, and that same greed is potent in every woman today. But the ballot box will put Delilahs out of the charmed circle. Education, political and economic freedom, have given woman a new key to triumph. She need no longer depend on man’s strength – her own is rising, Phoenix-like, from the ashes of repression.” Elsewhere, Theda said, “The vampire that I play is the vengeance of my sex upon its exploiters. You see, I have the face of a vampire, but the heart of a feministe.”

* * * * *

It’s an ironic fact that today Theda Bara is better known from still photos on the web than from her movies. Unlike film stars such as Greta Garbo, who managed the transition from silent movies to talkies, Theda Bara’s career is wholly silent. She made an incredibly explosive impact in half a decade, and then faded away (She had one major film role in 1925 and a short comedy role in 1926, both of them silent). Her visual impact to this day continues to be striking. She still radiates intrigue, seduction, mystery – and her image is resplendent with the Belle Epoque’s poetic romance of death. Her look seems clearly to have been an influence on the aesthetic of the punk, postpunk, and gothic rock scenes (vis-à-vis Siouxsie Sioux, Lydia Lunch, and others; the influence of silent film imagery on bands like Bauhaus and in the deathrock scenes is well known), and it’s again no little irony that she holds such a large influence on something that did not exist in her day (that is, pop music, or rock and roll, and the resulting late 20th century subcultures that those musical movements spawned – although several sheet-music songs were written about Theda in her lifetime).

Some other notes about Theda Bara:

- She was 29 years old when her first starring movie (A Fool There Was) came out. However, she said she was 24 and routinely shaved 5 – 7 years off her age. (Theda has continued to fool many; some sources still give her incorrect age.)

- Her real name was Theodosia Goodman until she legally changed it to Theda Bara in late 1917. Her stage name before starring in movies was Theodosia de Coppet.

- She wrote her 28th film, 1918’s The Soul of Buddha, placing her among early female screenwriters.

- Ninety percent of her movies are lost.

- From 1915 through 1919 Theda made about 10 movies per year.

- She went to college at the University of Cincinnati for two years. She’s one of the few (if not only) high-profile figures in early motion picture history to have a university education.

- Although it’s a much-publicized fact that her name is an anagram for “Arab Death,” this was belatedly discovered by press agents and was not by design. “Theda” had always been a nickname and “Bara” was a shortened form of a maternal family name, Baranger.

- The horror story and subsequent Night Gallery episode “The Girl with the Hungry Eyes” by Fritz Lieber, Jr. is based on Theda Bara. The story is about a psychic vampire whose hypnotic eyes are used by an ad agency to entrance customers. Lieber’s dad played Caesar in 1917’s Cleopatra and the writer met Theda Bara on the set as a child.

- The character Muriel Kane in F. Scott Fitzgerald’s second book, 1922’s The Beautiful and Damned, patterns her style and mannerisms on Theda Bara. In fact, Bara started a fad of dress and mannerisms among women in the 1910s and 1920s: would-be Theda Baras were called “baby vamps.” (Compare to the “baby bat” term in the goth scene, which designates a newcomer.) The flapper fad largely supplanted baby vamps, although they could still be found into the late 1920s. By the time Revlon came out with its “Vamp” line of cosmetics in 1940 the term mainly meant a darkly chic woman, bereft of the vaguely occult and “homewrecker” connotations of the 1910s.

- Theda Bara’s father was a Polish immigrant and her mother was of French and Swiss ancestry.

- Half of her movie career was spent on the East Coast, in New York City and Fort Lee, New Jersey. She didn’t move to Hollywood until the Summer of 1917. At that time the Los Angeles area was still in the process of becoming the place for movies, vying with Chicago, Philadelphia, and New York.

- Despite her vampy public persona, Theda maintained that really she was just “a nice Jewish girl from Cincinnati.” She was born in the Midwest.

- Also in spite of her public persona, Theda’s private life was scandal-free and conservative compared to many other Hollywood figures. She married only once, for 34 years (until her death), and had no children. Her favorite hobby was reading.

Author Joan Craig was interviewed by Oliver in December, 2016.

You knew Theda Bara as your auntie growing up. When did you come to fully realize that she was one of the pioneering figures of early American motion pictures? How did the Theda you know as an aunt contrast with her public vamp persona?

Joan Craig: I don’t think that I realized the enormous impact that she had to millions of people until the 1960’s. Towards the end of Theda’s life and when Theda realized that most of her films had been destroyed, she kept saying with sadness, “No-one will remember me!” Those words stayed with me all during my life. I wanted to preserve her memory.

Theda at home was always artistically active. She loved to have a party and to be a matchmaker! She with her husband Charles Brabin would perform many a Shakespeare scene when I was very young, just for me! I didn’t realize the magnitude of this until I was in high school. I was studying literature and realized I knew the words that I was reading. My favorite was The Raven by Edgar Allan Poe. We would get quite dramatic in reciting this together. I had no idea that this had anything to do with her films. Later in life I realized that my knowledge of Theda Bara was now historical and needed to be preserved.

Theda Bara seems ultimately to have enjoyed but also resented the typecasting she had as a vamp. On the one hand, her notoriety, fame, and wealth rested on it. On the other hand she seemed to feel boxed in by the typecasting. Did you get a sense of this ambivalence from Theda and how did she express it, or did you see it expressed?

Joan: Theda loved portraying all her characters. She was not internally conflicted with the roles that she played. Theda was absorbed into the psychology of man, as she would say. She would say a person has many personae (faces), and she loved the opportunity to explore and expose these characters. Theda did it so well no one would believe that she wasn’t really like her movie roles in real life. If Theda was seen walking down the street, people would grab their children and cross to the other side.

Theda would have liked to play a Mary Pickford, ingénue-type role but her public would not accept her as that character. She was upset by the fact that many of her acting roles were censored. She felt that the audiences were adults and should realize that she was an actress. Theda never left her house without wearing a veil over her face in public. This had been requested in her contract with Wm. Fox.

Your book fills in some important blindspots that other Theda Bara biographies either omit or got wrong. After her two years of college at the University of Cincinnati, from 1903-1905, many assumed she left immediately for NYC. Your book is the first to shed light on her going to Milwaukee and Chicago after her U. of Cincinnati days. When you read previous biographies did you ever think, “Oh no, these writers have gotten some things wrong?” Were you ever tempted to contact the writers to tell them they had written some things that were factually incorrect?

Joan: I purposely never read any other Theda Bara biography. I did not want to be discouraged in my heart by thinking I couldn’t write a good book, and I didn’t want to be influenced by others. After I wrote my book and looked at some other stories written about Theda, I didn’t want to tell others differently. Those authors wrote what they knew and interpreted. Theda did not publicly expose her time spent in Milwaukee and Chicago. While Theda was there she often worked as an usher so she could see the plays. In those days employees were often paid with stock certificates by their employer. It was verified when I personally returned her theater stock to the Pabst Theater after her death.

In your book you mention several times that Theda would cite bad karma when something bad happened. When she began to realize most of her films were lost, she called it (bad) karma. When her husband Charles Brabin’s stock certificates ended up being worthless due to the Great Depression, again she cited karma. And when she tried to show you a film of hers and it crumbled in the projector, she again cited karma. I find it incredibly sad that Theda may have died feeling like her legacy was lost, considering her importance. Did you get a sense that she felt regret that she might pass out of the pages of cinema history through all these losses? How did she express this?

Joan: Definitely! She would spend days reading quietly in her room while she was despondent and sulked over the loss of her movies. She felt that her films exposed truths. The films were important for audiences to see so people could recognize the psychology and not be so fooled!

How do you think Theda Bara would feel about the Theda renaissance we seem to now be undergoing? In the past twenty years, three major biographies (including yours) and a documentary movie have been made about her, and people are constantly trying to piece together aspects of her life and work to recover all they can. How do you think she would feel about folks doing this?

Joan: Theda would be so happy and very grateful.

It wasn’t until Hugh Munro Neely’s 2006 The Woman With the Hungry Eyes documentary that definite evidence was provided that Theda Bara had indeed spent some time in Paris in her 20s, which some writers thought was a fabrication. Did Theda ever tell you any stories about her brief time in Europe (like staying with the young Preston Sturges, or hanging out with Mary Desti and Isadora Duncan, etc.)?

Joan: It is true that Theda did spend no more than six months in Paris, as I recall. I was in the company of Theda and Charles when Charles interrogated Theda as to how she spent her time there. I cannot recall the exact conversation. The French actress Sarah Bernhardt was Theda’s idol and she met her in the US. The names you mention I can recall, however not with detail. Some of Theda’s films were filmed in foreign lands. She spoke seven languages fluently.

Some have noted that most people today know Theda Bara mainly through still photos. But those seem to have made quite an impression, and they seem to have obviously influenced some of the aesthetics of the punk, postpunk, and goth music genres. I’ve wondered what you think Theda would think about her image becoming so iconic, and what she would think about younger kids, especially in music, nowadays being fascinated with her look?

Joan: I think Theda would be very proud of these young people. Theda was truly an artist who was able by physical and facial expression to express the message in a photograph. She was modern and creative. Music is a creative message to the soul. Theda wanted to reach into the soul of the person with her pictures and still photos.

Did anyone “teach” Theda her trademark look and style? How did her look develop? I’ve always assumed it was a combination of the way one needed to look to register visually on early silent film prints as well as her own take on trying to look like, well, a “vampire.” Theda surely had a role in the creation of this look, as even after her career was over she seemed to still appear with what would now be called a “goth” look. Your thoughts?

Joan: As a young girl while assisting her mother in her wig shop, Theda at home brewed recipes to create powders and makeup for customers to look totally different. Theda owned a patent on her created makeups. Theda would ask me to look at the on-sale makeups to see if the name Bara was mentioned on the label in small print. Theda received an income from the various makeup companies, including Helena Rubinstein. Theda often said that she did not mind that Helena tried to take credit for her look because it was publicity.

About Theda’s influence on what is now called the goth look (but which in her day was called the “vamp” or even “baby vamp”) – do you think she would be proud?

Joan: Yes, she would be very proud. Theda believed that there is a “vamp” in every woman!

What did Theda Bara consider her greatest film, and do you know why?

Joan: Theda loved all of her films. She felt that each one portrayed a different message. Theda’s favorite was The Soul of Buddha that she authored while riding on the train from California to New York. She also spoke about The Eternal Sapho. She wanted her audiences to recognize the great wrongs in our souls. She wanted audiences to see it!

How did Theda feel about William Fox – did she ever say? I was disappointed to see that in Upton Sinclair’s 1933 interviews with Fox, Fox mentioned her maybe once and then only in passing as a single actress he had once-upon-a-time worked with, when in the mid-1910s everyone seems to agree she made the William Fox Studios into the Fox Films juggernaut it became.

Joan: Theda did not allow the name William Fox to be mentioned in her house!

How into the spiritualist side of things was she?

Joan: Theda was well versed on all religions. However, closest to her heart was her crystal ball, the Ouija Board, Tarot Cards and the spirits around her. She felt that her karma was from a former life.

What do you feel is a common misconception or error about Theda Bara that you would like to clear up for people?

Joan: Theda was a very quiet, reserved and well-educated individual. There was really only one man in her life and that was Charles Brabin, her husband.

* * * * *

Theda Bara, My Mentor: Under the Wing of Hollywood’s First Femme Fatale, by Joan Craig and Beverly Stout, was published last year by McFarland Books.

Phillip Dye is currently involved in a project to reconstruct the great lost 1917 film Cleopatra. There is a GoFundMe page here that explains the goal.

Footnotes

[1] Theda Bara had a walk-on/extra role in 1914’s The Stain.

[2] In 1925 Theda Bara starred in The Unchastened Woman, which at the time was billed as a comeback movie. The following year she appeared in a Hal Roach comedy, Madame Mystery. Madame Mystery also Oliver Hardy, of Laurel and Hardy fame; Stan Laurel was the director. Clips from this were used in a few other film “appearances” later in the decade.